The ultimate aim of the employment system is not to create a self. This is a long-forgotten aim in some distant, lost century. The aim now is to package the self, to create the illusion of a self in such a way that that self is appetising to those willing to try it out. This regime maintains a rigorous self-regulatory aspect: personal beliefs, political beliefs or criticisms are to be stored away in some private self, only to come out on weekends. A cognitive dissonance exists between the public and private, to the point where we feel an innate sense of inauthentic vibes emerging from those around us. Social discussion becomes a cheap relay of pre-packaged emotional responses, conventions and platitudes that seek not to provoke but to quell provocation, not to excite but to dampen excitement, not to bewilder but to normalize interaction.

In the employment system we take on the role of an obedient, subservient member of a team.

“In the course of playing social roles, people often come to internalize role-relevant personal characteristics. They come to see themselves as possessing the qualities suggested by the roles they play”.[1]

This is changing, with management theory revealing the benefits of democratic teamwork, devil’s advocacy in the workplace and the general positive results that emerge from negative critique. But basic social convention and interaction often stays the same for long after these new ‘techniques’ are introduced.

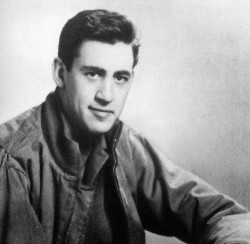

When J.D. Salinger wrote Catcher in the Rye in 1951, he spoke of the “phony” characteristics of people in his generation, in some respects he was talking about the disconnect between private and public self. Holden Caulfield himself presents well, adults praise him (consider the nuns and his aging professor) but he does not reveal who he is. His private self is a lot more hostile than his public self, to the extent that no one can assist him with his troubles – he feels alone and isolated. The book resonates with teenagers for precisely this reason. Salinger was hailed as the “voice of his generation.” But this praise remains incredibly ironic: he spent almost the entirety of his book criticising his generation. If he was the voice, where was the generation who followed his words with action? People still went on lying in interviews, dressing up who they were to impress others, putting on fake masks in different social settings depending on what was required of them.

When J.D. Salinger wrote Catcher in the Rye in 1951, he spoke of the “phony” characteristics of people in his generation, in some respects he was talking about the disconnect between private and public self. Holden Caulfield himself presents well, adults praise him (consider the nuns and his aging professor) but he does not reveal who he is. His private self is a lot more hostile than his public self, to the extent that no one can assist him with his troubles – he feels alone and isolated. The book resonates with teenagers for precisely this reason. Salinger was hailed as the “voice of his generation.” But this praise remains incredibly ironic: he spent almost the entirety of his book criticising his generation. If he was the voice, where was the generation who followed his words with action? People still went on lying in interviews, dressing up who they were to impress others, putting on fake masks in different social settings depending on what was required of them.

These were the same people who said the book “resonated” with them.

The danger in creating multiple selves has long been understood in psychology. Roy Baumeister says: “the concept of the self loses its meaning if a person has multiple selves…the essence of self involves integration of diverse experiences into a unity. In short, unity is one of the defining features of selfhood and identity.”

If this is true, how can someone even form a self within employment, if they are required to split their personality in two? The distinction between private and public selves has grown starker and starker as the years go by.

The dangers are more prevalent, because, “when we publicly state an opinion or behave in a given fashion, we are expected to be the person we claim to be”.[2] This issue raises a distinct possibility of cognitive dissonance. If we present only part of ourselves during our working lives, and then our colleagues expect us to be that person always – we are setting ourselves up to be oversimplified, and setting up them to be deceived.

It is becoming increasingly common for people to delete their social media accounts in the lead up to a round of interviews. This is exactly what I’m talking about. People are deleting their personalities to fit a proscribed job role – even when their personalities have nothing inherently offensive (or criminal, for instance) about them. Even when they are in almost every way: completely normal.

I asked someone who deleted their personality (both metaphorically through social media and in reality in the interview) why they did so. They answered: “Once I went to a job interview where they printed out my entire Twitter feed and went through it, comment by comment, asking me about every single Tweet. What I meant, what my views were, why I said what I said? In sum, questions that were completely irrelevant to whether I could do the job or not.”

People are so scared now of revealing their personal opinions on anything to their boss, be it religion, politics or otherwise, that they are willing to delete themselves to avoid the revelation. If they do reveal anything about themselves they run the risk of getting fired due to new standardized Australian contracts that ban people for talking about their work on social media: even if such discussion is in the public interest (consider corruption; sexism; racism or discrimination as examples, where public letters have done wonders for ending terrible practices).

The reality is that meaning comes foremost from self-definition and individualisation; the idea that we can gain meaning in conformity is anathema, mentally harmful and a damaging indictment on the level of doublethink our society has come to endorse.

We are what we create, and in our rush to create a self before we’re ready to do so –and I speak here of the tens if not hundreds of people I know unsure of what to do but still proclaiming their love of a profession in interviews- leaves us unfulfilled because the self we are presenting is not who we actually are. This trend doesn’t so much indicate a disconnection of the self; it indicates a disconnection from the self. What we are doing is separating ourselves from who we are for the tacit benefits that this process entails. We have locked up our individuality into the tightly confined boxes of our houses and expect that we will still be able to sustain meaning, fulfilment and self-esteem (from individual growth) outside of these boxes, even though honesty, frankness and free discussion are essential elements of individual growth. In other words, we are setting ourselves up for failure.

Worse than this is the persistent frequency with which this issue has been raised, time and time again, and consistently ignored, often provoking a vicious public backlash. Authors like Salinger, Bret Ellis, McInerney and David Leavitt were praised in their times as “voices of their generation”. But this praise was consistently met by a furious backlash against ‘whining’ and ‘complaining,’ also known as a backlash against caring and solving problems. The antithesis to a first world problem is a first world solution.

The gradual resolution that society has come to is an intermittent celebration of the dissenting voice. If too honest, too painful, to grow up with the realization that some of our most fundamental systems are structurally and fundamentally incorrect – then we later discard that old realisation. Inspiring authors get condemned to the category of “youth” and get proscribed as young texts aimed at “rebellious teenagers”. Instead of acknowledging criticism as valid, criticism gets acknowledged as “young”. Salinger and others get lumped in this box, ready to head out to the garbage collector.

The implication is that by the time someone reaches adulthood they should stop criticising systems at all – rebellion is for the youth. But the youth – despite popular mantra – have the least power to change anything: they have none of the levers of “50 years experience in X” that society so heavily endorses. The political class has moved beyond the fundamental questions of improving life, improving work and disimproving people’s ability to fake who they are, instead going on a tangential crusade about ‘workers rights,’ ‘jobs’ and dental.

Eight out of ten people hate their jobs. 64% of Australians are actively looking for new work. Free dental will not solve this: radical shifts in the way we practice our social interactions and the way we find meaning in our lives might.

But in the end, as much as we may condemn everyone else – we must ultimately take responsibility for how we are largely to blame. If there really are people who are the “voice of our generation,” then they remain powerless and frankly, pointless, if everyone else in the generation remains silent.

The ability to accept something like Catcher in the Rye as a great book one day, and lie in an interview the next, displays our inability to reconcile our values with our present-day reality.

To do so is quite simple: stop applying for jobs you don’t want. Only apply when you actually want something; be honest, care enough to tell an interviewer what you actually think.

The solution to being “phony,” as Salinger called it,

is being real.

———————————————————————-

[1] McCall & Simmons, 1966; Sarbin & Allen, 1968; Stryker & Statham, 1985

[2] (Goffman, 1959)