In 2023, Byung-Chul Han published Absence, a book that challenged the foundations of Western philosophy. He argues that while the West is obsessed with essence and being, Far Eastern thought is about absence and nothingness.

In its pursuit of being above all else, the West has lost something. The quiet of emptiness, the space for stillness that Eastern culture embraces as a source of depth, contemplation, and beauty.

Han’s critique speaks to the modern world we are living in today. The addiction to hypervisibility, productivity, and self-exposure. In the age of social media, every thought must be said, every moment recorded, and every individual reduced to a brand. We have become trapped in the presence of ourselves. There is no room for mystery, silence, or space to withdraw.

By contrast, Eastern philosophy places value on absence. This is reflected in the archetype of the wanderer—one who moves through the world without staying in any one place. Daoists describe the sage as one who “wanders where there is nothing at all.” The bird in flight “leaves no trail behind,” or “the good wanderer leaves no trace.” Japanese Zen master Dōgen has a similar teaching: “A Zen monk should be without fixed abode, like the clouds, and without fixed support, like water.”

Han contrasts this with the West’s addiction to accumulation of material belongings, and to our longing for permanence and legacy. Our digital world is the manifestation of this. It’s an endless flood of images, information, and self-expression. Documenting our lives, where nothing is ever allowed to be forgotten, where silence has been erased, to be replaced by ever-increasing noise.

In Absence, Han writes:

“The West fears emptiness, and so it fills everything. The East, in contrast, understands that emptiness is not nothingness but a space where meaning emerges.”

He applies this to everything from philosophy, to our very definition of time. The Western mind treats time as a resource—something to be optimized, filled, and accounted for. We are urged to “make the most” of every second, to “seize the day,” to leave no moment unproductive. By contrast, Eastern traditions, particularly Zen Buddhism, see time not as something to be controlled, but as something to be experienced. To sit in stillness, to watch a leaf drift in the wind, to do nothing. These are not wasted moments but acts of presence. Of being at one with the world and one’s surroundings. This is a deeper level of presence. It is reflected in Eastern traditions like meditation, fasting and contemplation in nature.

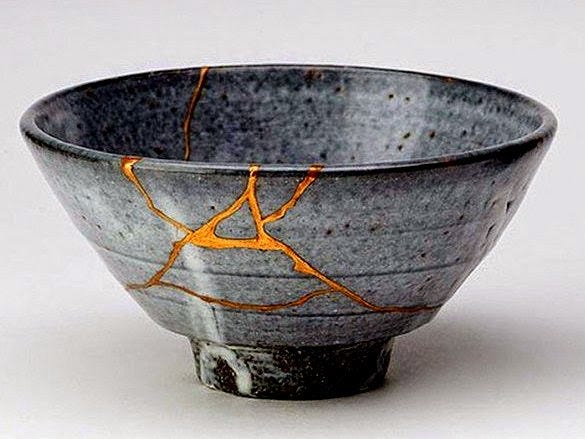

A world where everything must be seen is a world where nothing is understood. In traditional Japanese aesthetics, the concept of yūgen refers to a beauty that is hinted at rather than fully revealed. Like a mountain shrouded in mist, a poem that leaves its final meaning open. Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery. If a bowl is broken, rather than discarding the pieces, the fragments are put back together with a glue-like tree sap and the cracks are adorned with gold.

Ironically, it is through contemplating absence that we come to understand our existence. Through the holes and the gaps, the broken pieces and shattered pottery, we learn the beauty of the thing itself: the bowl, the self, and nature. Instead of perfecting and accumulating the world and its resources, we learn the benefits of being in harmony. In the Eastern tradition, Zhuangzi describes “ultimate happiness” as existing in harmony with absence—being directionless, without a fixed destination, like a blade of grass bending in the wind.

This contrasts with the Western ideal of happiness. In our modern world, we view happiness as the collection of material possessions, houses, cars, wealth and status. Even those of us who resist these urges, see happiness in terms of accomplishments, goals and objectives. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant, for example, describes it as follows:

“Filling our time by means of methodical, progressive occupations that lead to an important and intended end… is the only sure means of becoming happy with one’s life.”

At the root of western discontent is the belief that we must leave a mark upon the world, that we must impose our will upon nature, carve out a legacy, and be remembered. But in the Eastern tradition, the good wanderer leaves no trace. Not out of failure, but because they are moving in step with the world around them. They pass through without interruption. The Chinese poet Li Bai expresses it another way: “Heaven and earth, the whole cosmos—is just a guest house. It hosts all beings together.”

Byung-Chul Han takes this further, exploring how grief and absence gives our life meaning. He recalls the story of a kabuki actor who explains why he loves peonies, because they lose their petals in an instant. It is this, that makes them unique. “It is not only the full-blooming peony, in all its splendor, that is beautiful; what is most beautiful of all is the painful charm of its transience.”

The flower is not beautiful in its perfection—it is beautiful because it will soon be gone. In a world obsessed with permanence and visibility, absence is the one thing we have forgotten how to see. We want to preserve the perfect state, rather than realizing impermanence is what gives our lives meaning.

Han’s critique is radical in its simplicity: we must reclaim absence. We must learn to retreat, to embrace silence, to resist the demands to be always visible, always engaged, always present. True depth comes not from filling every space but from allowing space to exist. This is not an easy task. To step back from presence is to resist an entire cultural and technological system built on the demand for more.

But it is necessary. As Han reminds us, absence is not emptiness. It is a condition for true being. It is only in stepping away from the noise that we can begin to hear ourselves again.

Subscribe

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Follow me on Twitter: @JoshKrook

Subscribe to my video essay series on YouTube.