The future has never seemed closer, yet we’re still struggling to find our place in it. It’s no surprise, then, that many of us are turning back to the cyberpunk genre. Its’ a world of hackers, rebels, and misfits, in the form of new videogames, movies, and novels.

In a world increasingly captivated by technology, cyberpunk makes us consider the fringes, the outsiders, the rebels, the hackers—as a beacon of hope.

So today, let’s reconsider this genre that speaks to the challenges of our time.

This is Cyberpunk: The Philosophy of the Rebel.

The Core of Cyberpunk

At the heart of cyberpunk is a simple yet meaningful contrast: high-tech and low-life.

The technology in these worlds is incredibly advanced, but it exists in dystopian societies marked by extreme inequality and corruption. Low-life characters—hackers, misfits, mercenaries—are the ones who uncover the dark secrets of these tech-driven worlds. They act as rebels and outsiders who can reveal truths and offer hope, even when everything seems lost.

But before we look into themes, let’s consider the history of the genre.

Part 1: The History of Cyberpunk

In some ways, it began in 1959, when Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce invented the microchip. This revolutionized how we thought of the future of technology. Before this, science fiction portrayed computers as vast, intimidating machines—often occupying entire rooms. But with the microchip, that changed. Suddenly we could imagine a computer that can fit in your pocket, your hand, or even your brain, was within reach.

In the 1960s and 70s, fuelled by these inventions, science fiction entered what’s called the New Wave.

This era was marked by four key themes in books:

- The rise of an information economy and information warfare

- The hyper-commodification of culture

- The creation of synthetics, and the rise of simulated and virtual reality

- The concept of uploading consciousness— of separating our minds from our bodies

Up until this point, science fiction in the 1950s and 60s was largely optimistic. Technology was portrayed as a force for good. Robotic helpers who’d take care of our mundane tasks, allowing us to live lives of leisure and pleasure. There’d be the occasional conflict. But this was a cheery vision of the future where man triumphed over nature and subordinated technology.

But as technology leapt forward in the 70s and 80s, sci-fi began to shift its focus in a darker direction. Some of this shift was likely due to the Cold War. The threat of existential annihilation from nuclear weapons, along with the rapid advancement of military technologies.

In 1975, John Brunner released The Shockwave Rider, which many consider the first cyberpunk precursor novel. This book foreshadowed key ideas that would come to define the genre. It featured a near-future dystopia ruled by huge corporations, where consumer technologies mask the erosion of personal freedoms. In the book, “distributed desk computers” connect to a “data net”—a precursor to the modern internet. This data net is supposed to democratize information but ultimately, it merely reinforces existing societal inequalities.

These themes would lay the foundation for later cyberpunk novels.

Another core building block of cyberpunk was the 1970s and 80s rise of Asian technological supremacy, and the Western perception (if not fetishism) that Asia was the future of human progress and human society.

The 1980s saw the rise of cheap consumer electronics from Japan and China like the Walkman, introducing the idea of technology that was portable and wearable, creating a culture of individuality, mix tapes, music swapping and grunge fashion. In his frequently quoted preface to Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology from 1986, Bruce Sterling summarizes this change as follows:

‘Eighties tech sticks to the skin, responds to the touch: the personal computer, the Sony Walkman, the portable telephone, the soft contact lens.’

This was matched aesthetically by changes in architecture, in places like the densely urbanized Kowloon Walled City of Hong Kong. The Walled City being an oppressively densely populated space, with endless apartment blocks and concrete walls, crammed together with wires and bright lights. This and other scenes (e.g. the neon of Tokyo) inspired an Eastern fetishism. This can be seen in films like BladeRunner and the Fifth Element. The future was conceived of in these places as overpopulated, densely technological, and oppressively claustrophobic.

Finally, the 80s saw a shift in Western pop culture too. Eighties pop culture was dominated by a new aesthetic, visual and music movement. Rock videos, ‘the hacker underground, in the jarring street tech of hip-hop and scratch music, in the synthesizer rock of London and Tokyo’. Punk had a resurgence in these fringe subcultural movements, which eventually shifted towards mainstream mediums.

The Rise of Cyberpunk Writing in the 1980s

By the 1980s, a group of writers were growing increasingly disillusioned with the status quo of science fiction. Names like William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Lewis Shiner, Pat Cadigan, and Greg Bear were among the first to create stories of gritty, high-tech futures. These works were soon coined “cyberpunk”—a blend of “cybernetics” and “punk,” reflecting their technological focus and rebellious spirit. They embodied 1980s counterculture, fusing together ideas of the skater, the slacker, the hacker and the rock star into a singular image: the outsider in a Neo-noir world.

William Gibson’s Neuromancer was the first novel that cemented the genre, playing into a lot of these aesthetic features. In Neuromancer, we’re introduced to Case, a washed-up hacker who once ran the edges of cyberspace—what Gibson calls the “matrix.” After betraying his employers, Case’s nervous system was destroyed, leaving him unable to jack into cyberspace again. Now, crippled, addicted to drugs, and deep in debt, he drifts through the underworld of Chiba, Japan, hoping for a cure that will allow him to return to the digital world.

What he longs for is cyberspace, which he describes as:

“A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts… A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non-space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding…”

The Philosophy of the Rebel

Cyberpunk’s appeal is more than just its futuristic gadgets or neon-lit cityscapes however. It’s the philosophy of the rebel that drives the genre. In a world where technology often seems to control us, cyberpunk turns to the rebels, misfits, and outcasts because they are the characters who, despite their flaws and imperfections, can stand against the overwhelming forces of corporate control, surveillance, and inequality. It takes an outsider to understand how a system works, to see the rot, and to see the flaws.

The philosophy of cyberpunk is therefore the philosophy of counter-culture; the man against the machine, the David against Goliath. These works remind us that even in a world dominated by powerful tech, there’s still room for human resistance, for change, and for hope.

The rebels might not have all the answers. But they are at least asking the right questions. Questions about what it means to be human in a high-tech world, what it means to create, and what it means to love.

The Aesthetics of the Cyberpunk World

In visual media, cyberpunk is dominated by the long shadow of the greatest film in the genre: Bladerunner. Directed in 1982 by Ridley Scott, Bladerunner embodied the cyberpunk aesthetic for the first time in film, showing: mean streets, neon lights, effervescent advertising, smoke, high-tech robots and simulations. It has since received a sequel, covering the same aesthetic and the same philosophical question. What does it mean be a human, and what does it mean to be a machine?

In Blade Runner, Rick Deckard (played by Harrison Ford), is a retired cop, pulled back into action by his police boss to hunt down a group of escaped replicants. These are genetically engineered humanoids created by the Tyrell Corporation. These replicants, led by Roy Batty, have returned to Earth, and Deckard’s mission is to “retire” them before they cause any more trouble.

As Deckard begins the hunt, he encounters Rachael, Tyrell’s assistant, who is revealed to be a replicant herself, though she doesn’t know it. Tyrell has implanted fake memories to make her believe that she’s human. This discovery leads to a complex relationship between Deckard and Rachael. He grows conflicted feelings about his mission and begins to question his own identity.

Throughout the film, Deckard uses a test to determine if someone is a human or a replicant, making use of various emotional and physical ques: mainly related to empathy. In the novel upon which the film is based, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Deckard is asked at various points whether he has used the test on himself. It is heavily implied, in both the novel and the director’s cut of the film, that Deckard might be a replicant, with false, implanted memories.

As the story unfolds, Deckard’s understanding of what it means to be human becomes increasingly blurred, as he begins to see the replicants, particularly Roy Batty, not as mere machines but as beings with a profound desire for life, freedom, and identity. In the culminating chapter, Roy Batty reflects on the life he has lived, revealing that he might not be too different from a human after all:

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion… I watched sea-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain…

The film raises deep questions about humanity, memory, and what it means to live a meaningful life. All of these questions take on a starker tint when examined in the neon light of a digital dystopia.

While Blade Runner is a cornerstone of cyberpunk, its primary contribution is often seen as aesthetic rather than thematic. Its focus on humanity, technology, and simulacra is philosophically rich, but cyberpunk as a genre often embraces an indifference to how “human” someone is, leaning more into how much “Chrome” they have.

The Philosophy of Transhumanism

Cyberpunk was one of the first sub-genres to focus on transhumanism – the idea that we can ‘evolve’ beyond our human physical form through technological augmentation.

The cyberpunk world is a world of cyborgs – entities that are part-human and part-machine. Thematically, this means transcending the limitations of the human condition, suspending our consciousness through machinery or becoming super-humanly strong through cybernetic enhancements to the body. It also means machines that have human characteristics – through biological implants, memory uploads or other material derived from human life.

Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 film, Ghost in the Shell (based on the Manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow) – covers this theme in detail and is celebrated as a classic – one of the first Japanese works in the genre to reach a mainstream Western audience.

The film is set in 2029 in the fictional New Port City and follows Major Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg public-security agent who hunts an enigmatic hacker/ghost known as “the Puppet Master”. The narrative incorporates philosophical themes that focus on self and identity in a technologically advanced world. The music, composed by Kenji Kawai, includes vocals in classical Japanese.

The story begins as follows:

Major Motoko Kusanagi follows a request from Nakamura, chief of Section 6, to successfully assassinate a diplomat of a foreign country to prevent a programmer named Daita from defecting to that country. The Foreign Minister’s interpreter however, is ghost-hacked (taken over), presumably to assassinate VIPs in an upcoming meeting.

Believing the perpetrator to be the mysterious Puppet Master, Kusanagi’s team follows the traced telephone call that sent the virus. After a chase, they capture a garbageman and a thug. However, both are only ghost-hacked individuals with no clue about the Puppet Master, so the investigation again comes to a dead end.

Ghost in the Shell is made up of characters who are cyborgs: whose bodies are replaced by prosthetic parts which enable incredible physical and cognitive abilities, and access to a vast information network. However, these advantages come with a cost. The access to information leaves them open to being ‘hacked’ by an external party. This means losing complete control of their brain or being implanted with false memories to replace their actual ones.

This results in a second major problem for the cyborgs: a form of existential dread. How can they know for sure what’s real or what isn’t, whether they are human or machine? The protagonist Major Motoko Kusanagi says at one point: ‘Sometimes I wonder if I’ve already died and what I think of as ‘me’ isn’t really just an artificial personality comprised of a prosthetic body and a cyberbrain.’

In Shirow’s original manga, the cyborg body challenges the liberal humanist notion of what it means to be a human being, by questioning the Cartesian duality of mind/body, subject/object. Famously, the philosopher Descartes poses the theory: ‘I think therefore I am’. However, this theory only holds true if one’s thoughts are one’s own. For a cyborg, the thought could come from someone else, radically undermining the mind/body connection.

In a confrontation with the Puppet Master, Kusanagi has the following revealing conversation:

- Major Motoko Kusanagi: You talk about redefining my identity. I want a guarantee that I can still be myself.

- Puppet Master: There isn’t one. Why would you wish to? All things change in a dynamic environment. Your effort to remain what you are is what limits you.

Transhumanism at its core therefore has this idea of the world and the self being in a constant state of flux. Unsurprisingly, therefore, it is a part of cyberpunk that has been heavily embraced by both the feminist and trans movements. Donna Haraway, in her cyborg manifesto, makes the case that the cyborg is a character who is beyond traditional ideas of gender: neither man nor woman, merely machine.

Transhumanism is also a transcendence of the self. The cyborg is no longer an individual identity. Instead, through their connection with the information system, they become ‘one with the many’. Their identity blurs into the information system, their memories blur with others, and they abolish the sense of self that underpins the human condition.

In this way, Ghost in the Shell argues that it is our memory and body, our physiology, that makes us human. One of the most memorable quotes of the film goes as follows:

Major Motoko Kusanagi: There are countless ingredients that make up the human body and mind, like all the components that make up me as an individual with my own personality. Sure I have a face and voice to distinguish myself from others, but my thoughts and memories are unique only to me, and I carry a sense of my own destiny. Each of those things are just a small part of it. I collect information to use in my own way. All of that blends to create a mixture that forms me and gives rise to my conscience. I feel confined, only free to expand myself within boundaries.

The finale of Ghost in the Shell envisions a merging of human consciousness with artificial life: the ultimate blurring of boundaries. As we head in our own time towards increased access to AI systems, we should carefully consider the implications of human/AI connections, what it means to be a human being, and whether we might leave anything behind in our race to the future.

Cyberpunk: Revolution or Just Keeping the Boys Satisfied?

Cyberpunk as a genre has faced its fair share of criticism. Chief amongst these are a lack of female representation and its arguably bleak outlook on the future, which some argue undermines its social impact (it is hard to be a nihilistic rebel). In fact, many believe the movement has been co-opted by the very corporate forces it initially set out to critique, falling from a counter-cultural movement, to yet another neoliberal art form.

Let’s start with representation. Women were largely excluded from early Cyberpunk narratives. For example, Mirrorshades, the influential short story anthology that helped define the genre, included only one female author: Pat Cadigan. This lack of diversity led to long-standing critiques that Cyberpunk wasn’t truly countercultural at all. If it couldn’t even have strong female characters, then how was it an anti-conservative movement?

In 1992, Nicola Nixon addressed this in her article “Cyberpunk: Preparing the Ground for Revolution or Keeping the Boys Satisfied?” She argued that despite its edgy, rebellious aesthetic, Cyberpunk was anything but radical. Instead, she described it as complicit with the conservative, male-dominated culture of the 1980s. Other critics have also pointed out the lack of strong female characters and LGBTQ perspectives in the early cyberpunk works, questioning the genre’s claim to subversiveness.

Another critique is that Cyberpunk has become too mainstream over time. By the early 1990s, what started as a revolutionary movement had, according to some, devolved into a predictable formula: biological computer chips, corporate dystopias, leather-clad antiheroes, and decaying orbital colonies. Lewis Shiner captured this in his New York Times piece “Confessions of an Ex-Cyberpunk,” sadly reflecting that the genre had traded its rebellious roots for commercial appeal.

This corporatization reached a new level with the release of Cyberpunk 2077, a Triple A video game title. While visually impressive, the game has been criticized for stripping the “punk” out of Cyberpunk, offering a world drenched in corporate aesthetics but lacking the revolutionary ethos that once defined the genre.

‘Punk is about nonconformity and anti-authoritarianism,’ writes Stacey Haley in her PC Games Review, ‘It’s DIY, it’s anti-consumerist, it’s anti corporate greed. It stands for taking direct action and not ever being a sell-out. Cyberpunk – the genre – twists these ideals around futuristic dystopian settings, in which individuality is about rebellion against state suppression, not merely looking cool. I’m not sure if a triple-A game could ever truly capture the essence of [the cyberpunk genre], when self promotion and mass-market appeal fly in the face of punk’s ethos. But this game and its promotion seem to eschew everything its genre namesake is meant to signify.’

Glitzy titles like Cyberpunk 2077 merely pay homage to the visual aesthetic of cyberpunk while stripping away its core message: a critique of capitalism and greed. In the game, you play as V, an individualistic mercenary who over time, ingratiates himself to various factions. And while it pays homage to rock music and other icons of the genre, it never lives up to the counter-cultural current of challenging authority and power. Indeed, even the character creator struggles to give an array of interesting choices to the Player. In the end, V doesn’t resist the matrix, he becomes its embodiment: a disembodied individualist in a sea of greed.

This criticism of cyberpunk has gone so far as to spawn an entirely new, opposing genre called Solarpunk.

Solarpunk: A Bright Vision for the Future

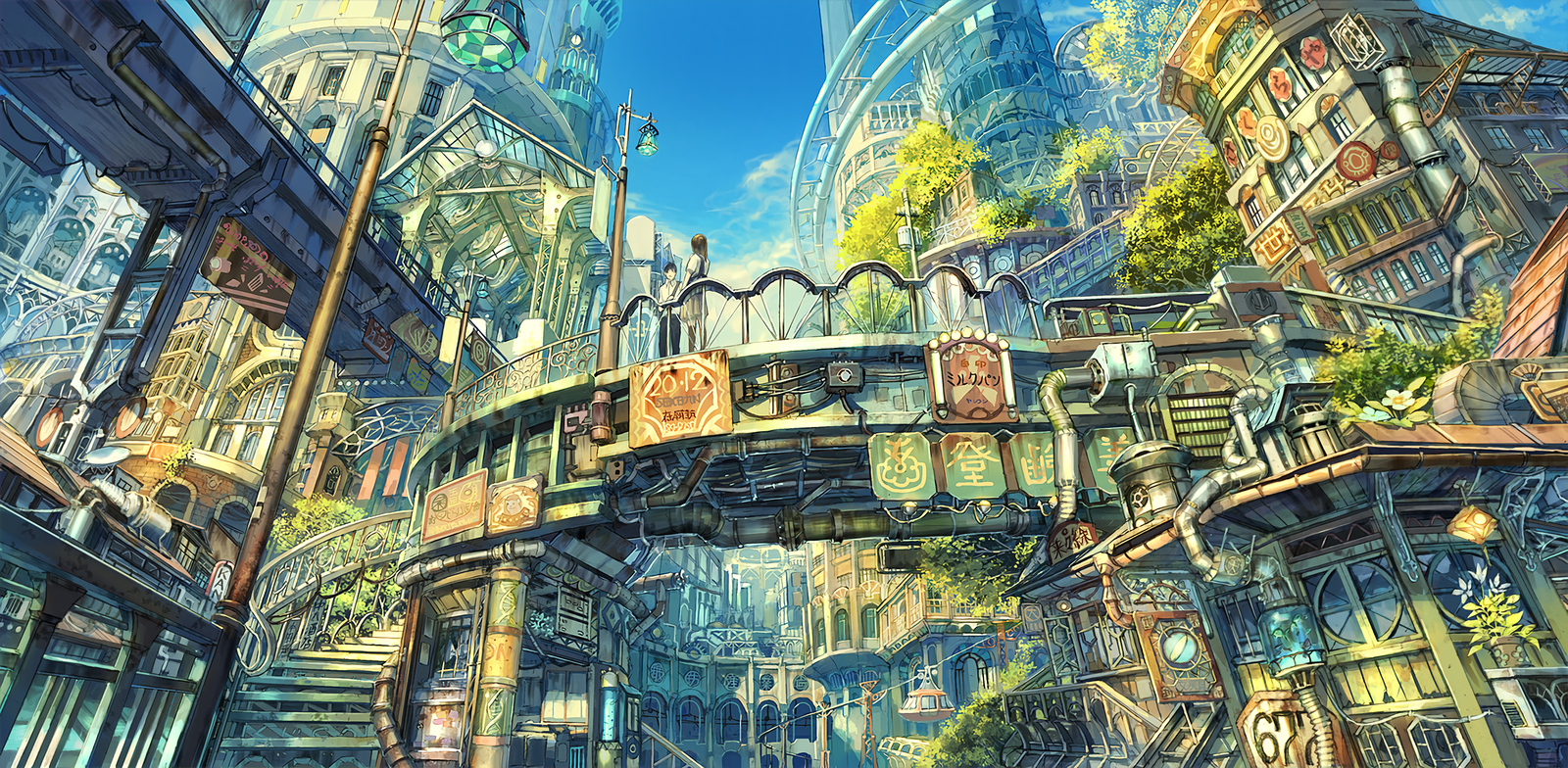

Solarpunk presents an optimistic and inspiring vision of the future, offering a sharp contrast to the dark and dystopian themes often associated with Cyberpunk. Instead of focusing on corporate greed and social inequality, Solarpunk imagines a world where technology, humanity, and nature coexist harmoniously. It’s a genre and a movement that emphasizes sustainability, renewable energy, and community-driven solutions to global challenges.

At the heart of Solarpunk is a commitment to sustainability, where resources are used responsibly to protect the environment for future generations. This vision is powered by renewable energy, with clean sources like solar and wind providing the foundation for technological and social advancements. Solarpunk worlds are often depicted as lush and green, blending futuristic architecture with thriving ecosystems. This aesthetic reflects the genre’s core belief that progress doesn’t have to come at the expense of the planet.

Another central theme of Solarpunk is community building. Unlike the isolated, fragmented societies of dystopian fiction, Solarpunk emphasizes collaboration and equity. In these imagined futures, people work together to create inclusive and resilient communities where everyone’s needs are met. This cooperative spirit is complemented by technological optimism—the belief that innovation can be a powerful tool for solving humanity’s most pressing problems, from climate change to social inequality.

Stories like The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower showcase these ideals in action. They depict futures where creativity, resilience, and collective effort transform adversity into opportunity, proving that a better world is not only possible but achievable.

Ultimately, Solarpunk is more than just a genre of speculative fiction; it’s a call to action. By showing us a future where human ingenuity and environmental stewardship go hand in hand, it inspires us to reimagine what progress can look like. Solarpunk reminds us that the choices we make today shape the world we’ll leave for tomorrow—and that with enough imagination and determination, we can build a brighter, more sustainable future.

–

Subscribe to the blog to follow future essays.

Some of this was inspired by the The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture (2019).

For the YouTube version see: