It’s becoming increasingly difficult as time progresses for humanity to have any connection to nature. And almost to solidify this, a lot of the books written on the subject seem to us to be some misguided attempt to strip away the modern pleasures that we enjoy – technology, entertainment and lifestyle.

We rebel against the onslaught of nature-purists in our lives, as if they are Birnam Wood marching on Dunsinane Hill, as in Macbeth.

But what is often lost in this discussion is that nature is not vying for our attention or demanding anything from us (unlike the media, advertisement and the entertainment industry) but instead always remains in the background, awaiting like a long lost friend, our attention to reignite the friendship once again – for free.

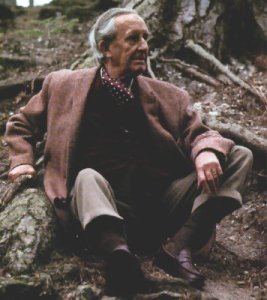

To us, it seems strange to think of the love J.R.R. Tolkein had for nature, to use an example.

Tolkein had an almost anti-industrialist view of the world, seeing the fires of World War II and mirroring them in his books. His Ents, walking tree-people, marching to war (mirroring Macbeth) were then and now a potent symbol of the revenge of nature for being ignored, burned, and plundered.

But it’s a warning from some long lost century.

There is a strangely sterile and alien way in which we’ve moved beyond that –that youthful play and joy in nature- to our boxed in, hemmed up, hawed off lifestyles as adults.

As children, the connection was easy – sport is a universally mandated activity at a young age and it was simple to be out there, amongst it all, without any great effort.

On holidays, on days when we could steal from studying, we escaped on wild rambles across the countryside; we needed fresh air, full sun, lost paths at the bottom of gullies, which we claimed as conquerors.

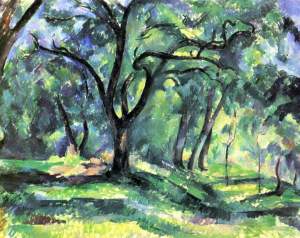

Passages like these, on the youth of Cezanne in Aix en Provence, reignite some of that fervour.

But as we age, the fervour disappears.

It is as if we are afraid that the unpredictability of nature could influence the stability of our adult lives. Where we must, to maintain those lives, remain secure, upstanding and respectful; nature is restless, tumultuous and crazy, in its wild, unpredictable way.

This movement of nature is a fear – and we avoid it, even while at the same time our lives are ruled by chaotic, wild social forces that cannot be avoided at all.

I dream of long reveries under the sky, of verses that unroll with a great noise of wings. And I see once more the greenery, the scorching plains overcome with the intense heat, the far horizons that hardly contained the proud ambition of our sixteen years..

When we look back at the great artists and the works they did (aside from those of a religious nature) we find that nature is a dominant subject. In some ways this is surprising to a modern audience. It as if we expect our TV’s to have brighter, and more vivid colours than the actual environment that they depict. But when we read the biographies of the artists themselves (Cezanne’s is one I recently read), we encounter the reason why they dwelt upon the subject of nature to begin with: to capture a greater realism of the world. To actually picture something, whether in our minds, or on television and film, we have to be there and see it, experience it, feel it. And it is this great disconnect that is taking place in our modern world where we are expected to experience everything from afar, whether it be the creation of the products in our lives; our own productions in our workplaces, or the calming embrace of nature that used to be a daily escape for people just a mere century ago.