(Cite as: Krook, Joshua. 2025. “Building Serendipity into Recommender Algorithms on Online Platforms: Reviving the Chaos and Randomness of the Early Internet Aesthetic”. Law, Technology and Humans, January. https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.3730.)

Abstract:

Nostalgic comments about the early internet often praise its random, chaotic aesthetic. By contrast, the major platforms of today are typically viewed as corporate in aesthetic, with a one-size-fits-all profile, and personalized recommendations of products. The curated life is the opposite of the serendipitous life. Instead of seeing strange or unusual items, online algorithms have been shown to trap users into ‘you loops,’ surrounded by similar users in filter bubbles. Algorithms on major platforms give the illusion that users are getting what they want, yet users often complain of a form of aesthetic sameness, blandness and repetition to the products they see and get recommended.

In this paper, I consider forms of resistance against algorithmic ranking and efficiency, including nostalgia for the early internet. This includes a consideration of early websites that were more chaotic compared to the algorithmic ranking-based sites of today. I argue that the movement towards a curated life has resulted in a loss of serendipity for the user and the narrowing of the user experience, limiting personal growth and the variety of content users are exposed to. This ‘narrowing’ effect contributes to a flattening of culture, where culture starts to reflect what the algorithm rewards. I consider ways to shift back to a more random aesthetic, where less popular items are sometimes shown to the user, to increase the serendipity they experience on major platforms.

Introduction:

In 2011, the University of Sydney began removing books from Fisher Library to make room for new laptop study spaces. The librarian John Shipp had the difficult task of deciding which books would stay on campus and which books would be shipped off to a remote, off-site storage facility. To determine which books would go, he invented the notorious “dust test.” Any books found to have a layer of dust on them would be removed from the campus library, while commonly used books would remain on the shelves. Dusty books would still be available via retrieval from an online catalogue. However, students would have to request for the books to be physically brought back to them on campus. This meant that you could no longer accidentally stumble upon these obscure volumes on the shelves. You needed to know what you were looking for.

By the end of “the dust test” process, over 500, 000 books, nearly half of the library’s collection, was transferred off-site. The library was transformed overnight, from a place of discovery and exploration to a largely digital space, with smooth, seamless study spaces, gleaming white desks and nap pods (Figure 1). Gone were the obscure history tomes, replaced by textbooks and popular novels. Previously, visiting the library involved losing yourself in the shelves, stumbling upon a few random texts, perhaps unrelated to the field you were studying, and learning something new. What “the dust test” killed was the serendipity of finding the unexpected, to be replaced by the dull predictability of the common, the popular and the mundane.

Figure 1: A Malfunctioning ‘Sleep Pod’ in Sydney’s Revamped Fisher Library.

Image Credit: Author’s Photo. 2019.

“The dust test” is a fitting ethnographic story for the digital age we are living in today, where digitalization attempts to make all processes smooth, efficient and seamless, at the expense of interruption, accident and surprise. Online platforms have the same problem as the overcrowded library: they contain millions of items that must be sorted and ranked for users to see, with some items needing to be hidden from view. The internet’s librarian is the recommender system. These powerful algorithms make decisions on which items should be shown to users, and which items are “too dusty” to show on screen. “Dusty” items are hidden behind search bars or obscure menu options, where users need to manually search for them.

Over time, these algorithms have begun to ‘curate’ the user experience, in order to increase platform efficiency. The push towards efficiency can be contrasted against the chaotic nature of life prior to digitalization. Anne Helen Petersen tells a relevant story of looking for a friend on a college campus in the early 2000s. It was a time before mobile phones, social media, or a digital camera. If she wanted to find a friend on campus, she had to simply “walk around.” Typically, what followed was an odyssey: walking through the campus’ halls, checking dorm rooms, visiting the library to ask if anyone had seen the friend in question. Sometimes, they were found quickly, other times the search turned into a “college night picaresque with distractions (shitty nachos) and diversions (good gossip, a random dance party).” Petersen never knew if the night would work out: “there was so much less control, so much less ability to curate what your night would look like.” Walking through the halls and bumping into strangers, there was a chance for new friendships or new romantic relationships. All of this felt more alive, fulfilling and joyful than the “sterile world of infinite choice” facing her online today.

The curated life is the opposite of the serendipitous life. By serendipity, I refer to “the finding of unexpected information (relevant to the goal or not)”. Curation, by contrast, refers to a pre-planned show or display, or an ordering or structuring of items to view. Recommender systems move our lives away from serendipity and towards curation by structuring, ranking and organizing the content we are exposed to. This occurs via personalization, which removes the unexpected surprise of unusual items that do not fit our expected taste. Algorithms have the same biases as the “dust test” of Fisher Library, with a tendency to prioritise popular items, incumbency, and homogeneity, over variation and difference. In this way, they lead to the same drawbacks of diminishing serendipitous encounters. Netflix, for example, recommends new TV shows based on a user’s past viewing history, including what TV shows they clicked on, how long they watched for, and what similar users have watched in the past.

Recommender algorithms create a feedback loop for new titles that reinforces a feeling of sameness and repetition: a user will see: “because you watched Mission Impossible… here are other movies featuring Tom Cruise,” and therefore will watch a similar movie again. This new movie gets fed back into the system, reinforcing the feedback loop. Meanwhile, genres that the user does not engage with frequently are hidden from view. The recommendations resemble a mirror or a “you loop”: reflecting back opinions, entertainment and content that we already like and agree with. In this way, the curated life leads us towards a lack of personal growth, change or transformation. Instead of seeing different content and learning something new, we see content that confirms our existing beliefs. We get trapped into a ‘filter bubble’ or a ‘neighbourhood’ surrounded by other, similar users. Personalization filters out the different, so that we are less exposed to views and opinions that are different to our own.

The decline of serendipity online has correlated with the decline of shared spaces of people radically different from one another in the same viewing space. Traditionally, viewers would watch the same TV show at the same time on television, for example, whereas today, they stream personally recommended TV shows on Netflix at their own leisure. This decline of the ‘shared viewing experience’ extends to the graphical user interface: Netflix transforms TV and film posters to suit the viewing profile of the specific user. A user who watches romantic films will see new movie posters featuring romance, while a user who watches action films will see the same movies with more action-heavy posters. Curation of the user experience limits the opportunity of the user to extend beyond their usual watching patterns. Instead, they are psychologically primed to reinforce their pre-existing behaviours.

In the following section, I consider forms of resistance against algorithmic ranking and efficiency, including nostalgia for the early internet. This includes a consideration of early websites that were more chaotic in nature compared to the algorithmic rankings of today. I argue that the movement towards curation has resulted in a loss of serendipity for the user and the narrowing of the user experience, limiting their growth and the variety of content they are exposed to. I then consider ways to move back to a more random content format, while retaining some of the advantages of digitisation and (some of) the efficiency gains provided by recommender systems.

Disturbing the Dust: Resistance to Efficient Design

“We’re going to go and disturb the dust,” Jo Ball said, ”I don’t think books should have an expiry date.” Following the announcement of “the dust test” at Fisher Library, Jo Ball, a history graduate, organized a student protest movement to “disturb” the dusty books. Ball began by setting up a Facebook page, organizing an event titled: “Save the books! Disturb the dust! Mass book borrowing action this Wednesday.” University students were encouraged to borrow the maximum number of books allowable on their library cards, with the intent of disrupting the university’s book transferring process. John Shipp, the librarian, had mentioned that any books not borrowed in the last five years would be removed from the library. The students organized to borrow all of these books from the library at once. If enough books were borrowed, their thinking went, the library would be saved.

Ms. Ball’s protest was doomed to failure, as the university had already started the book removal process. Nevertheless, the fact that a student rebellion occurred at all provides a fascinating ethnographic moment of resistance to digitalization, change and efficiency. Consider the fact: students were fighting to keep books on campus that they rarely, if ever, read. The university was instigating digitalization to make the library more efficient, introducing new laptop study spaces, a new café, and making room for popular textbooks, and updating the online catalogue. Ball’s protest represented a resistance to this process of ordering and structure, and a preference for the chaos of the library of old. One of the central complaints of these students was that removing the books would be bad for researchers. “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking,” writes Japanese author Haruki Murakami.

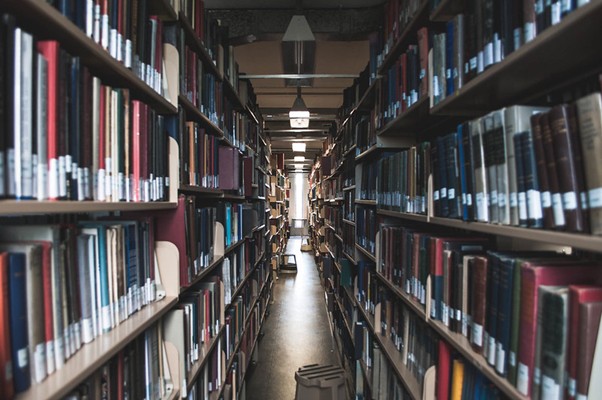

Fisher Library had always been a densely populated space, riddled with books in tightly crammed shelves, triggering disability and Occupational, Health and Safety (OH&S) concerns. The narrow ‘stacks’, as students called them, barely had room for two people to move between abreast (Figure 2). There were rumours of students making out between the stacks at midnight, away from the prowling eyes of campus security. Even then, there was a charm to the chaos and the teeming volumes on the shelves. It was the lack of organization that students were searching for. The burgeoning shelves promised that you might find something that you were not looking for. There was a lack of organization: unread volumes appeared side-by-side with staple textbooks, merely sorted in alphabetical or thematic order. A “random” element still existed, in that the thematic texts contained rare or unusual books that defied neat categorisation.

Figure 2: The Fisher Library ‘Stacks’ prior to dust testing.

Image Credit: Jen Y, 2013.

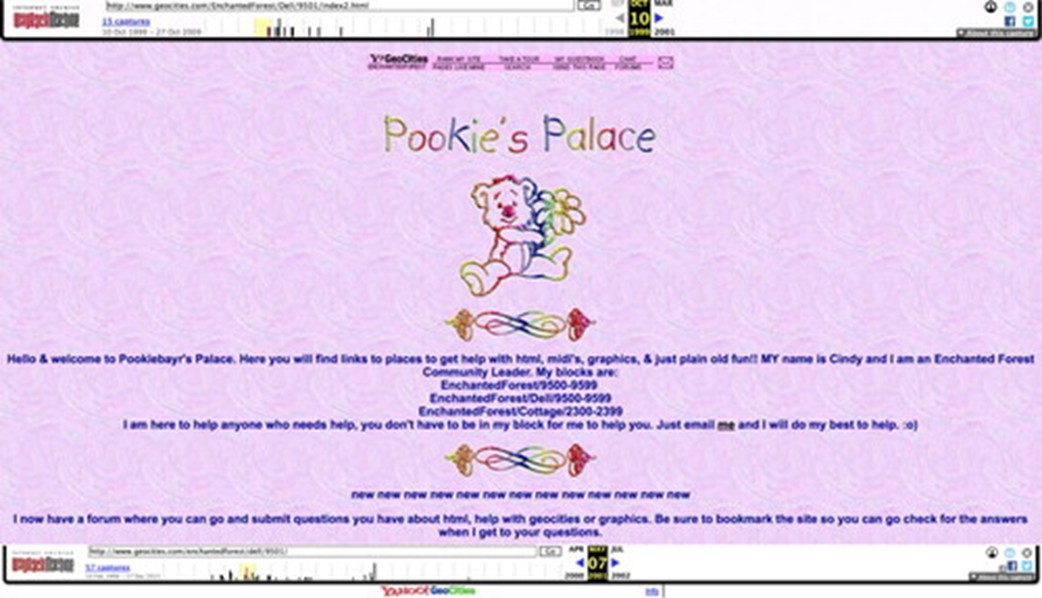

Fisher Library’s transformation mirrors the ongoing transformation of the online world. The internet too, has dealt with a burgeoning volume of items, and undergone a similar change: from chronological feeds showing everything, to algorithmic recommenders preferencing some content and hiding others. The early internet is celebrated in popular media as a time of radical serendipity, where users experienced the chaotic randomness of life, but in an online format. Commentators describe the early internet of the 1990s and 2000s in nostalgic terms as “a giant treasure hunt,” “full of excitement to discover new things,” “rough [and] frontier-like,” more “joyful,” and with a fun aesthetic quality. Some of this might be overstated. What is true is that the early internet encouraged users to individually express themselves in stranger ways than the modern form: creating their own websites, forums, and later, blogs. Before the rise of social media, a homespun aesthetic dominated the primitive online landscape with websites like Geocities and MySpace allowing users to create their own profiles, with their own images, music and animation.

Nostalgia for the early internet revolves around this serendipity and a backlash against the newly algorithmic (and therefore more predictable) feeds. An analysis of nostalgic tweets about Myspace, for example, finds that users celebrated its “chaotic aesthetic” and the “dominance of people of colour and young women”. One user writes: “sweet, smiling Tom… never rearranged a timeline,” celebrating the lack of algorithmic curation on this platform. At times, these sites came across as childish, strange, oblique or niche, but also precisely because of this, they rarely fit into the neat, tidy, corporate aesthetic of a Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn profile. These were the sites that existed when the internet was “individualized and amateurish,” but not yet personalized.

Geocities.com allowed users to build their own websites with bright colours, star banners, music and other features that allowed a higher degree of self-expression. Pookie’s Palace a site from 1999, welcomed visitors “with a swirling purple background, a rainbow teddy bear and neon text” (Figure 3). Following the demise of Geocities as a platform, archives and artistic reproductions have been created in its image. Cameron Askin, a New Zealand Artist, created one such aesthetic display with Cameron’s World: a “web-collage of text and images excavated from the buried neighbourhoods of archived GeoCities pages (1994–2009).” He writes: “In an age where we interact primarily with branded and marketed web content, Cameron’s World is a tribute to the lost days of unrefined self-expression”. The archive celebrates the “weird” of the early internet, lionized as a time before people used their real names to associate with their social media.

The oblique nature of these early websites contributed to a feeling of randomness. Without the constraints of platform dominance, users were radically empowered to control their own environment. Craigslist, which started in the late 1990s, was the epitome of this early internet aesthetic. The site resisted calls from venture capitalists, paid advertising and changes to its graphical user interface to modernize. First started as a mail-in service posted online as a newsletter, it morphed into a website where individuals would post random items for sale, jobs and classifieds. The items were disorganized. The site retains its goal of being an un-curated place of discovery, where users picked the categories they wanted and saw a full catalogue of items, rather than filtering items through a curated feed.

Where newer forums like Reddit curate the user experience with upvoting, downvoting and algorithmic suggestions of new subreddits to follow, early websites showed the latest posts in purely chronological order. This meant everyone’s comments appeared as soon as they were posted. There was no filtering or moderator preview. There was less focus on the most popular or engaging items, and more focus on strange postings. The chaotic nature of the early internet mirrored the chaotic nature of life. As compared to LinkedIn, for example, with its corporate chic aesthetic and ‘correct’ way to post (praise your boss and company, appeal to status, thank mentors), early internet forums rebelled in their eccentric style, their abandonment of authority and moderation. Jokes, memes, and off-topic posts were more common, although some amount of content moderation did occur. As one user reflects: “early 2000’s forums were the best… like before Reddit and other social media and smartphones took off.” The allure of these early forums was the randomness of their structure and the democratic nature of their discussion.

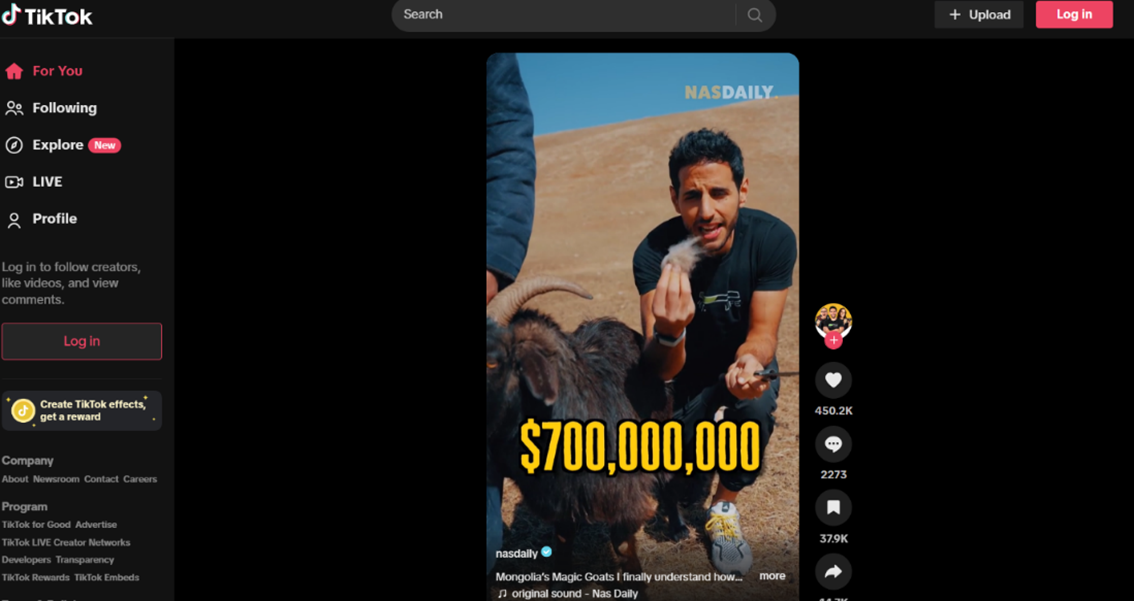

The evolution of the internet away from chaos and towards a corporate order seems to mirror the evolution of culture William Deresiewicz describes at American colleges: “now students all seem to be converging on the same self, the successful upper-middle-class professional, impersonating the adult they’ve already decided they want to become.” Websites too, followed this shift in aesthetics. From the chaos of GeoCities came the relevant order of MySpace, and the substantial order of Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn profiles: where everyone has the same profile, with only different photographs to populate it. The shift towards popularity meant that these sites now appealed aesthetically to as many people as possible. This is visually clear when comparing a GeoCities site (Figure 3) to the most dominant platform among young people today, TikTok (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Homepage of Pookie’s Palace Website. 1999.

Image Credit: Author screenshot. Wayback Machine. October 10th, 1999.

Figure 4. Homepage of TikTok. 2024.

Image Credit: Author screenshot. June 16th 2024.

In the mid-2010s, Facebook, Instagram and other social media sites started shifting their algorithms away from a chronological feed and towards algorithmic engagement via recommendations. Now, users no longer saw posts as they were posted, but instead saw the “most engaging” content. Jack Conte, CEO of Patreon, marks this as the turning point of internet culture, where the major platforms turned their backs on content creators, preferencing engagement statistics to keep people hooked to their platforms for the benefit of advertising revenue. Previously, users saw content they subscribed to, using the ubiquitous “Subscription” button on YouTube and other sites. Now, even content users subscribe to was hidden if it was not popular or engaging enough, effectively negating the user’s own choice. The CEO of Meta, Mark Zuckerberg, reveals that Facebook and Instagram have changed to follow this trend. Now, around “30% of the posts on the Facebook feed” and “more than 50% of the content people see on Instagram is… AI recommended”. This is a substantial shift from the earlier chronological feeds of these platforms, which lacked AI recommenders. Instead of showing users what they choose to see via subscription, platforms now recommend content that they think will be engaging to the user, sacrificing autonomy for efficiency.

Previously, chronological feeds retained a character of randomness and chaos; users were exposed to everything posted recently, rather than only the most popular posts. Now, users are faced with the most engaging posts, limiting their exposure to a diverse set of content. This has two significant effects. Firstly, it cuts users off from different users and traps them into a filter bubble filled only with those who are similar to themselves (in interests, likes, and engagement data). Secondly, it traps them into what Byung-Chul Han terms the “you loop”. The longer a user spends on a platform, the more the recommender system learns what they like, the more it recommends to the same the same content. Eventually, all other content is filtered out. The user is left with a kind of mirror-reflection of themselves: a platform that shows them things that they already like, that they already agree with, and that they already have engaged with before. By nature, this is a stifling of intellectual progression and growth: the progression moves towards further sameness, rather than further difference.

This is significant precisely because recommender systems are so ubiquitous today. Algorithmic recommenders now suggest, in part, what news we read, what movies we watch, and what romantic partners we match with on dating apps. They make these decisions based on user data, negating explicit human input. On Spotify, songs are chosen for the listener automatically (although this sometimes exposes them to new music). On TikTok, videos are chosen for the user without any need for the user to subscribe to any channel that they want to follow. The “subscription” model is completely replaced in this instance by the algorithm: so the user asserts no agency over the platform. Instead the platform asserts agency over the user: telling them that these are the products they are interested in.

Unlike previous “knowledge-based” recommender systems, newer algorithms do not ask the user what they want – they show the users what they are presumed to want based on their implicit data and behaviour on the platform. TikTok is a radical break from the subscription model, where users at least got to choose who they follow. The entire TikTok interface is built around its “For You” algorithm. The algorithm optimizes for user retention and time spent on the app, according to a leaked memo. In this way, engagement becomes the number one factor for how the app is designed, rather than considering whether the user can grow or change by using the app to discover new content. This automation of choice and decision-making may abolish individual agency. When the user loses the ability to choose, they also lose the ability to choose the unexpected: the algorithm predicts their preferences rather than providing them with the full range of opportunities. This results in a loss of serendipity. As a result, curation can narrow the user experience, by trapping users into their own reflection.

Chayka suggests that we now live in a “vast, interlocking and yet diffuse network of algorithms that influence our lives,” which has simultaneously created a more “homogenous” culture that “perpetuates itself to the point of boredom.” Visual artists must now consider the Instagram algorithm when they make their work, while songwriters tailor their song-writing to the algorithm of TikTok. Charlie Puth breaks down his songwriting into tiny ten-second videos to appeal to his TikTok audience – a process he does not enjoy doing. While at the same time, an “Airbnb aesthetic” has started to influence interior design decisions in a lot of popular holiday destinations across Europe. This algorithmic sameness creates the flattening of culture – where difference in culture are ironed out for the purposes of efficiency: for quickly renting out that top Airbnb location.

Far from a serendipitous space, algorithms therefore provide us with a space of personalized content verging towards sameness, showing us content that we already expect to receive, and therefore (eventually) triggering a form of predictability and boredom. Simultaneously, recommender systems make consumers more “passive” in their entertainment experience, and less capable of thinking about the culture they are consuming. On Spotify, where songs are chosen for the user automatically, the user does not engage in the “browsing” process for a new playlist, foregoing choice for the app’s decision-making. Users are empowered to curate their own playlists, but even here, the app suggests songs for users to add to their list (often of a similar nature or genre). This abolishes the serendipity of the prior experience in a record store or CD store. There, a consumer would have to browse the shelves and physically pick up the record that they wanted to listen to. This gave them the opportunity to walk past something new – a different genre that they rarely if ever listened to.

When an algorithm optimizes for engagement, it creates ideas that “are as acceptable as possible to as many people as possible.” In other words, it flattens culture and trends towards the average. Critics describe TikTok as “vulgar” and “kitsch,” referring to its highly-engaging, popular short-form video content of people binge-eating, mimicking popular dance crazes or binge-drinking alcohol. The company admits that they have had an impact on culture and user behaviour, including exposing users to new music and influencing what users recommend to their friends. Among Gen Z, “I saw this on TikTok” has become a popular catch-phrase. What gets lost in the wash of this is the homespun DIY nature of an earlier internet age, the unified sense of the world having the same factual foundation, a shared entertainment culture, or a shared online culture at all.

Re-Building Serendipity Online:

Designers of recommender systems can take a few key lessons away from nostalgic user reflections of the early internet, and the student resistance movement against the “dust test” at Fisher Library. Firstly, some users enjoy the randomness and chance that the early internet gave to their lives, the feeling of being on the frontier, with new and unexpected discoveries behind every corner. Second, some users consider the algorithmic re-ordering of their lives bland, repetitive or simply less exciting than the internet of the past, including the joys and unexpectedness of the chronological feed. Thirdly, the aesthetic quality of the early internet and Fisher library, with its chaotic shelves, is an aesthetic that can inspire a feeling of discovery and exploration. Finally, empowering users to control their own experiences online can enhance the serendipity they experience, including modes of self-expression that have since gone out of fashion. If each user can express themselves in more unique ways, this diversifies the content of the internet for every other user.

Recommender systems could be redesigned to place serendipity at the heart of the user experience. This includes periodically including more random items in the feed, that is at minimum, preventing users from being shown the same item many times, and going beyond popular items. Instead, the algorithm could be biased towards increased novelty, serendipity and an element of randomness – unexpected items or less popular items being shown more often. That is, showing users content from new genres, categories or themes and actually asking them – would you like to see more diverse content on your feed? Finally, from a cultural diversity perspective, designers could be encouraged to move away from a purely consumption (and attention) focus of their apps, and towards a more educational or intrinsic purpose, such as an art gallery featuring a broader diversity of items to its audience, to increase their understanding of the world around them. While many go to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa, the museum itself features thousands of paintings that are just as striking, if not more so, in the rooms surrounding the popular artwork.

Some call these diverse items the long tail. Since recommender systems typically prioritize popular items, this can create a “long tail” effect of lesser-known items in the catalogue. These are ‘dusty’ items that never get borrowed, because people do not know that they exist. In this case, the algorithm can be adjusted to place a higher focus on these lesser-known items, and simultaneously improve the profits of the company. Long-tail items provide an opportunity to target niche products to niche consumers, who are otherwise left out by popular items. Netflix’s recommender system was based on this long tail design methodology in its original conception. This made use of a huge catalogue of film and TV items appeal to the individual user. However, long tail methodology can still result in trapping users into a few key genres (even while showing them niche products of that genre). The methodology of the long tail must therefore be balanced with the need for individual diversity in recommendations: expanding the lives of the users by showing them more variety, and reinstating that feeling of surprise and adventure.

A few years after graduating, I returned to Fisher Library. In many ways, it was unrecognizable from the days I studied there. The nap pods that had been installed were malfunctioning (Figure 1), the students were left sprawled across the library amidst a sea of laptops on gleaming white tables, and the stacks that I remembered were gone, replaced by orderly rows of books at a greater (more OH&S compliant) distance. Entire sections of the library that had once held books were replaced, a new café stood in the middle of the room, and I listened to the hum and hiss of the coffee percolating. It struck me, looking at the students studying there, that perhaps they didn’t understand what they had missed out on; the joy of discovery, getting lost amidst the shelves in the middle of a project, finding something new and obscure. Instead, amid the sea of those studying, were the handful on TikTok, or Instagram, getting fed content by the machine that had been so accurately and diligently trained on their personal data.

Bibliography

Akira the Don. [@akirathedon]. [Tweet]. August 17, 2018. https://twitter.com/akirathedon/status/1030495910386515969

André, Paul, M.C. Schraefel, Jaime Teevan, and Susan T. Dumais. “Discovery Is Never by Chance: Designing for (Un)Serendipity.” In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 305–14. New York, USA, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1145/1640233.1640279.

Cao, Steffi. “A Nostalgic Look Back at When the Internet Still Felt Joyful.” CNN, March 14, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/03/14/style/lan-party-online-gamers-photos/index.html.

Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication, “CARGC Symposium – Turning Points: The Long 1990s in Internet History | Annenberg.” October 16, 2024. https://www.asc.upenn.edu/news-events/events/cargc-symposium-turning-points-long-1990s-internet-history.

Chayka, Kyle. Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture, New York: Doubleday Books, 2024.

Conte, Jack, Death of the Follower & the Future of Creativity on the Web with Jack Conte. SXSW 2024 Keynote, SXSW. 2024.

Dash, Anil. “The Web We Lost – Anil Dash,” Anil Dash (Blog). December 13, 2012. https://www.anildash.com//2012/12/13/the_web_we_lost/.

Deng, Jireh, “Meta Now Has an AI Chatbot. Experts Say Get Ready for More AI-Powered Social Media.” Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2024. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2024-05-02/ai-chatbots-come-to-meta-more-social-media.

Deresiewicz, William, Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014.

Dever, Ally, “How TikTok Has Changed the Music Industry,” CU Boulder Today, September 12, 2022. https://www.colorado.edu/today/2022/09/12/how-tiktok-has-changed-music-industry

Diniz, Rodrigo, “The Charm of Internet Nostalgia and Why It Isn’t Fun Anymore.” LinkedIn. April 15, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/charm-internet-nostalgia-why-isnt-fun-anymore-rodrigo-diniz-uto2c/.

Gomez-Uribe, Carlos A., and Neil Hunt. “The Netflix Recommender System: Algorithms, Business Value, and Innovation.” ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 6, no. 4. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2843948.

Fletcher, Amelia, Peter L. Ormosi and Rahul Savani, “Recommender Systems and Supplier Competition on Platforms,” SSRN Working Paper (2022).

Foulonneau, Muriel, Valentin Groues, Yannick Naudet and Max Chevalier, “Chapter 4: Recommender Systems and Diversity: Taking Advantage of the Long Tail and the Diversity of Recommendation Lists” in Recommender Systems, edited by Gérald Kembellec, Ghislaine Chartron and Imad Saleh, John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Han, Byung-Chul. Non-Things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld. Cambridge: Polity, 2022.

Han, Byung-Chul. Infocracy: Digitization and the Crisis of Democracy. Cambridge: Polity, 2022.

Jansson, Johan. “The Online Forum as a Digital Space of Curation.” Geoforum, 115–24, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.008.

Krook, Joshua and Jan Blockx. “Recommender Systems, Autonomy and User Engagement.” In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Trustworthy Autonomous Systems (TAS ’23). ACM, New York, NY, USA, Article 18, 1–9. 2023.

Lingel, Jessa. An Internet for the People: The Politics and Promise of Craigslist. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022.

Loder, D. “The aesthetics of digital intimacy: Resisting Airbnb’s datafication of the interior.” Interiors, 11(2–3), 282–308. 2021.

Mackinnon, Katie. “The Death of GeoCities: Seeking Destruction and Platform Eulogies in Web Archives.” Internet Histories 6, no. 1–2, 237–52. 2022.

Madden, Emma. “We Found Love in a Fictional Place.” The Outline. December 18, 2019. https://theoutline.com/post/8442/internet-nostalgia-2010s-geocities-tumblr-vaporwave.

Magagnoli, Paolo. “The Internet as Ruin: Nostalgia for the Early World Wide Web in Contemporary Art.” Transformations, 28. 2016.

McRae, Sarah. “‘Under Construction’ Lives: Restorative Nostalgia and the GeoCities Archive.” European Journal of Life Writing 8. 2019.

Millecamp, Martijn, Nyi Nyi Htun, Yucheng Jin, and Katrien Verbert. “Controlling Spotify Recommendations: Effects of Personal Characteristics on Music Recommender User Interfaces.” In Proceedings of the 26th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, 101–9. UMAP ’18. New York, USA: ACM, 2018.

Miltner, Kate M., and Ysabel Gerrard. “‘Tom Had Us All Doing Front-End Web Development’: A Nostalgic (Re)Imagining of Myspace.” Internet Histories 6, no. 1–2. 48–67. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2021.1985836.

Murakami, Haruki. Norwegian Wood. New York: Random House. 2011.

Narushima, Yuko. “You Can Judge a Book by Its ‘Dust Test’ as University Library Cuts Its Staff and Stock.” The Sydney Morning Herald, May 11, 2011. https://www.smh.com.au/education/you-can-judge-a-book-by-its-dust-test-as-university-library-cuts-its-staff-and-stock-20110511-1ej0z.html.

Narushima, Yuko. “Students plan dust-up with uni over library’s book cull.” The Sydney Morning Herald, May 13, 2011. https://www.smh.com.au/education/students-plan-dust-up-with-uni-over-librarys-book-cull-20110512-1ektk.html.

Nikolakopoulos, Athanasios N., Xia Ning, Christian Desrosiers, and George Karypis. “Trust Your Neighbors: A Comprehensive Survey of Neighborhood-Based Methods for Recommender Systems” In Recommender Systems Handbook, edited by Francesco Ricci, Lior Rokach and Bracha Shapira, 39-89. Boston: Springer, 2022.

Pajkovic, Niko. “Algorithms and Taste-Making: Exposing the Netflix Recommender System’s Operational Logics.” Convergence 28, no. 1. 214–35. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211014464.

Pearce, Gary. “The Curious Case of Shrinking Libraries, Coffee Carts and ‘the Dust Test’.” ABC News. May 25, 2011. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-05-25/pearcecoffee/2730066.

Petersen, Anne Helen. “The Sterile World of Infinite Choice.” Culture Study (blog), August 30, 2023. https://annehelen.substack.com/p/the-sterile-world-of-infinite-choice.

Ricci, Francesco, Lior Rokach and Bracha Shapira. “Introduction.” In Recommender Systems Handbook, edited by Francesco Ricci, Lior Rokach and Bracha Shapira, 1-35. Boston: Springer, 2022.

ResetEra. “Forum Culture from the Early 2000’s,” January 9, 2021. https://www.resetera.com/threads/forum-culture-from-the-early-2000%E2%80%99s.358474/

Smith, Ben. “How TikTok Reads Your Mind.” The New York Times, December 6, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html.

Szablewicz, Marcella. “Internet Cafés: Nostalgia, Sociality, and Stigma.” In Mapping Digital Game Culture in China: From Internet Addicts to Esports Athletes, edited by Marcella Szablewicz, 29–49. Springer International Publishing, 2020.

TikTok. “New Studies Quantify TikTok’s Growing Impact on Culture and Music,” TikTok NewsRoom. August 16, 2019. https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/new-studies-quantify-tiktoks-growing-impact-on-culture-and-music?

Wang, Jianling, Ziwei Zhu, and James Caverlee. “User Recommendation in Content Curation Platforms.” In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 627–35. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3336191.3371822

Wirawan, Shandy. “The Nostalgic Feelings of The Old Internet.” Medium (blog), September 8, 2023. https://medium.com/@shandywirawan/the-nostalgic-feelings-of-the-old-internet-bae70749c0ac.

Chen, Xi, and Huang Zeng. “Analysis of Media’s Effect on People’s Aesthetic: A Case Study on Tiktok.” Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 9. 120–26. 2023.