What makes art truly great? What gives it the power to move us, to linger in our minds long after we’ve seen it? There’s something universal in the way we respond to beauty, to grand vistas, and mystery. Something that transcends time and culture. Something called the Sublime.

Even in an age dominated by digital media and algorithms that favour fear and controversy… studies have shown that awe-inspiring content is shared more frequently than fear-driven content. This suggests an innate human longing: to be transported, to feel small in the face of something vast, and to witness the extraordinary and magical in the world around us.

As an Ancient Greek writer puts it:

Nature determined man to be no low or ignoble animal; but introducing us into life and this entire universe as into some vast assemblage, to be spectators, in a sort, of her entirety, and most ardent competitors, did then implant in our souls an invincible and eternal love of that which is great and, by our own standard, more devine. Therefore it is, that for the speculation and thought which are within the scope of human endeavour not all the universe together is sufficient, our conceptions often pass beyond the bounds which limit it; and if a man were to look upon life all around, and see how in all things the extraordinary, the great, the beautiful stand supreme, he will at once know for what ends we have been born.

On Great Writing (On the Sublime) 1st Century AD

The Artist and His World

Few artists have captured this sense of the sublime quite like Maxfield Parrish. Born in 1870 in Pennsylvania, Parrish was raised in an artistic and intellectual household. His father, Stephen Parrish, a well-known artist, and his mother, Elizabeth Bancroft, an engraver. He was raised in a Quaker society. As a child he began drawing for his own amusement, showed talent, and his parents encouraged him.

As a teenager, Parrish travelled Europe with his parents. There, sketching and absorbing the grandeur of classical architecture and the Old Masters.

This formative experience shaped his artistic vision for the rest of his life. Not just to depict the world but to elevate it into something transcendent. Something that went beyond the ordinary life we experience. In illustrated letters that he sent home to his cousin between 1884 and 1886, we can see this early talent and invention at work.

Parrish went on to study architecture at Haverford College. He studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, under Robert Vonnoh and Thomas Pollock Anshutz. He would continue his education in art at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry.

Artistic Style

Parrish’s illustrations are unmistakable. They are ethereal landscapes bathed in light; figures suspended in moments of quiet reverie. His technique involved layering glazes of pigment and varnish to create colours so vivid they seem to glow from within.

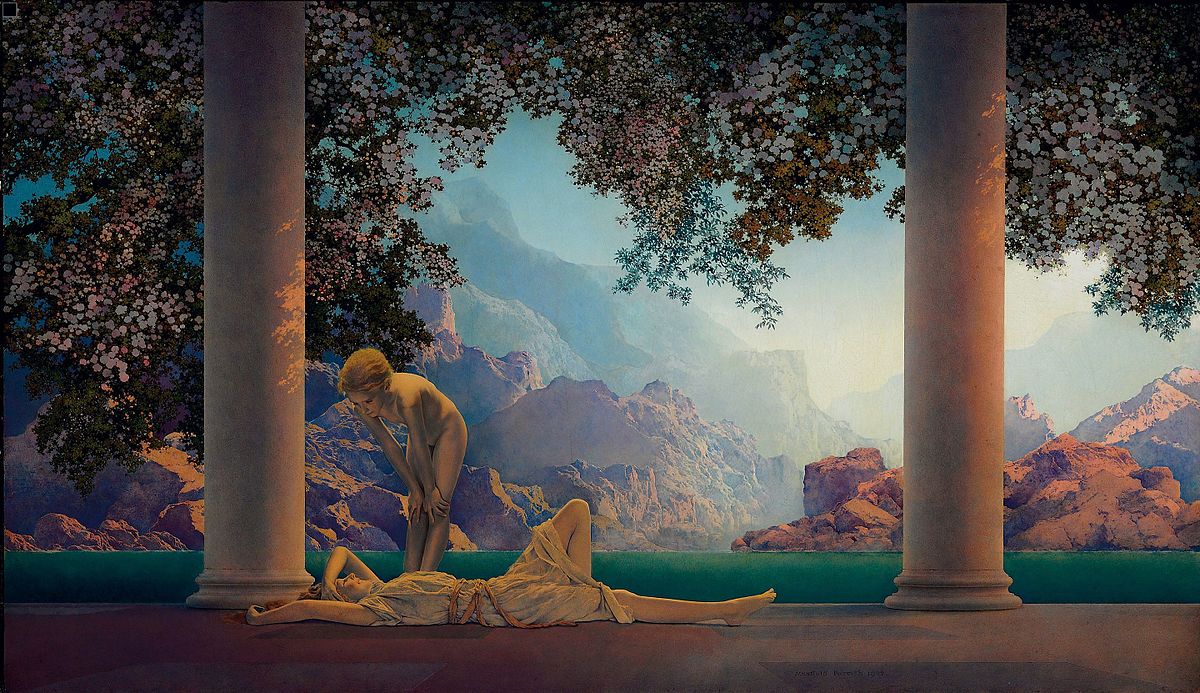

This use of colour, space, landscape and form, made him one of the most successful illustrators of all time. One of his most iconic works, Daybreak, became the most successful art print of the 20th century. It had widespread commercial appeal and sales figures. According to Alma Gilbert, the House of Art, which handled the printing, an estimated 1 out of every 4 homes in America had a copy of the artwork.

Decades later, its influence resurfaced in unexpected places. From Michael Jackson’s music video for You Are Not Alone to high-profile art auctions, where the original commanded $7.6 million, a record at the time. The works showed great popularity precisely because they seemed to depict something surreal and sublime. Our world, but shown in a new way, stunning and fragmentary in colour and obscured by light.

Use of Glazing

Indeed, a key component of Parrish’s signature style was the fantastic use of light and color. He was the proponent of many innovative techniques that involved the use of glazing. His artworks involved a painstaking process involving numerous layers of glazing applied in an alternating fashion with a pure pigment of bright varnish.

Therefore, the result was an incredibly saturated and mesmerizing effect. Parrish would also superimpose pictures of subjects onto his canvas and then cover them with glaze to create a striking three-dimensional effect.

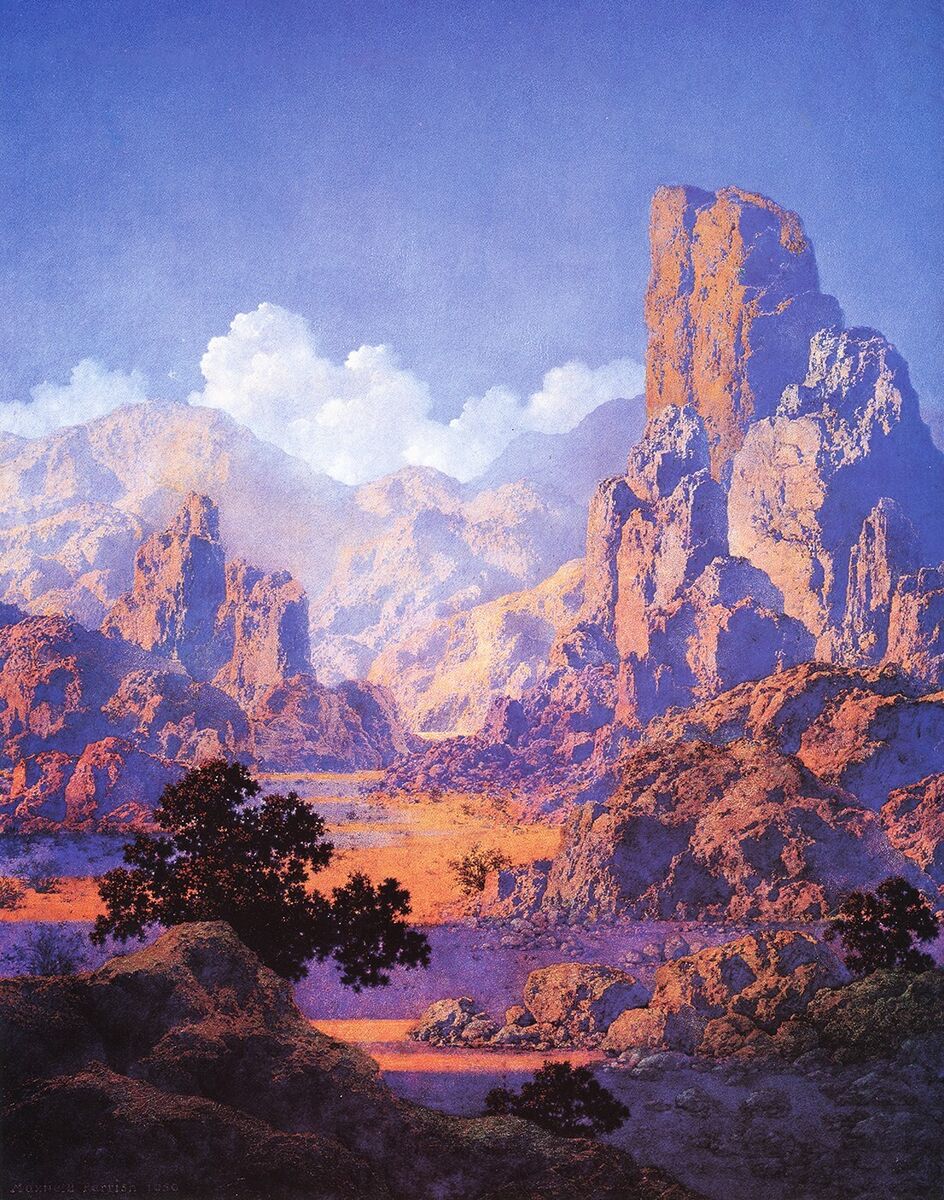

He was and still is associated with a particularly vibrant shade of blue that blanketed the skies of his landscapes. Although you will only rarely see a glimpse of that color in reality. And it was not easy for him to render. He devised a laborious technique using base of cobalt blue and white undercoating. Which he then glazed with a number of thin alternating coats of oil and varnish. The particular resins he used, called Damar, are known to floresce a shade of yellow-green when exposed to ultraviolet light. This gives the unique turquoise hue to the painted sky.

His signature use of this color was so powerful that a certain cobalt blue became known as “Parrish Blue,” and is still known as such in many painting shops.

The Man Behind the Paintings

Maxfield Parrish’s career was defined by two distinct phases.

The first saw him creating romantic, otherworldly scenes populated by elegant figures, often women in contemplative poses. These figures and character studies were immensely popular. But by 1931, he had grown tired of figurative work, famously stating, “I’m done with girls on rocks. I have painted them for thirteen years and I could paint them for thirteen more. That’s the peril of the commercial art game. It tempts a man to repeat himself.”

He then turned exclusively to painting landscapes, a passion that sustained him until his final years. This started with a collaboration with the calendar publisher, Brown and Bigelow. They continued publishing his work in their calendars until 1962. During those years, they printed more than 50 of his landscapes, although by the 1950s, public interest in his work had waned.

Self-Doubt and Insecurities

Yet, despite his immense popularity, Parrish struggled with self-doubt throughout his life. In a letter to an aspiring artist, he confessed:

It’s a grand profession. But oh. The discouragements! You have to live constantly with the consciousness of your own limitations, and your thoughts and visions are all so far ahead of your ability to portray them. I sometimes think that all the joy we get is just in the work, a ray of hope that maybe next time the thing can be grasped, or one can come a little nearer.

– Maxfield Parrish

More than fifty years after his death, Parrish’s art still holds power. His dreamlike- landscapes continue to captivate the imagination and the soul. They are reminding us that art can be more than just an escape. It can be an invitation to wonder about what it means to be a human being.

He painted his last picture at the age of 91, a landscape called “Getting Away From it All,” that still had his signature effects and impressions.

The Sublime as Human Experience

Parrish embodied the ideals of the sublime, that aspect of feeling something bigger than the self, associated with grand vistas, mountains and lake sides.

Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.

Immanuel Kant

The sublime is not just a concept in art. It’s a feeling and an experience. It’s what separates the ordinary from the extraordinary, the mundane from the magical. It’s what lingers in the mind, long after the paint has dried and the painter who painted it has died and past on. As Parrish himself stated:

“The hard part is how to plan a picture so as to give to others what has happened to you. To render in paint an experience, to suggest the sense of light and color, of air and space.”