In a world threatened by ecological collapse and corporate domination, Solarpunk offers an alternative vision for the future —one of resilience, cooperation, and harmony with nature. It is a genre that moves beyond dystopian cynicism, towards the ideals of the dreamer, the builder, and hope.

So today, let’s consider this genre that speaks to the challenges of our time.

This is Solarpunk: The Philosophy of the Dreamer.

The Core of Solarpunk

At the heart of Solarpunk is a simple idea: that technology can enhance our connection with nature, rather than destroying it.

Technology in these future worlds is advanced, but it exists in societies that prioritize sustainability, decentralization, and social justice.

Solarpunk characters—scientists, artists, engineers, and activists—are the ones who uncover the secrets of ecological restoration and community-driven change, overcoming the challenges of environmental destruction, climate change and war.

They act as visionaries and builders, demonstrating that even in the face of an environmental crisis, a future with nature is possible.

But before we explore these themes, let’s consider the history of the genre.

Part 1: The History of Solarpunk

In some ways, Solarpunk began in the 1970s, when the environmental movement gained widespread media attention. The oil crises, pollution disasters, and climate change debate fuelled a growing awareness of humanity’s impact on the planet. The extinction of animal species gained further recognition, along with humanity’s harm of the Ozone layer.

Science fiction in the 70s often focused on these dystopian consequences—nuclear war, ecological ruin, and corporate dominance. But alongside these bleak visions, a quieter movement was brewing: one that imagined a future where humanity could live in balance with the Earth.

The 1980s and 90s saw the rise of Cyberpunk, which examined how unchecked corporate power and technology could lead to inequality, environmental collapse and alienation. I’ve covered Cyberpunk in a previous video.

However, cyberpunk rarely presented solutions—it warned us of the problems but left the rebellion in a morally grey area. By contrast, Solarpunk emerged as a response to Cyberpunk, offering not only a critique but a blueprint for a better world.

The term “Solarpunk” was coined in 2008 in a blog post titled From Steampunk to Solarpunk, where an anonymous writer discussed the MS Beluga Skysails—the world’s first ship partially powered by computer-controlled kites. The word itself blends Solar—symbolizing renewable energy and environmental awareness—with Punk, representing resistance to oppressive systems and a commitment to grassroots change.

A year later, literary publicist Matt Staggs introduced the GreenPunk Manifesto, which shared similar ideas. He envisioned GreenPunk as a movement emphasizing individual agency in fostering ecological and social change.

Rejecting steampunk’s romanticism while embracing its appreciation for accessible technology, he described it as a world where consumer culture is reclaimed by the masses to restore the environment and address societal challenges.

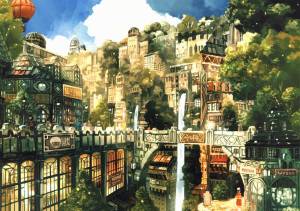

In 2014, visual artist Olivia Louise expanded on these ideas through artwork shared on Tumblr, shaping the aesthetic foundation of Solarpunk beyond just literature. She imagined a future inspired by updated Art Nouveau, Victorian, and Edwardian designs, infused with sustainable energy, technological literacy, and a revival of artisanal craftsmanship.

She envisioned:

- Natural colors and Art Nouveau influences

- Handcrafted goods and skilled artisans

- Streetcars, airships, and stained-glass solar panels

- Education for children in both technology and food cultivation

- A shift from corporate capitalism to small businesses

- Green rooftops, communal gardens, and renewable-powered cities

- Walkable streets lined with independent shops

- A blend of sustainability, technology, and stunning design

Through these ideas, Solarpunk offers more than just an aesthetic—it proposes a tangible, optimistic alternative to dystopian futures, advocating for a world where technology and nature thrive together.

The Rise of Solarpunk Writing in the 2010s

By the 2010s, a new wave of writers and artists grew increasingly frustrated with dystopian science fiction’s fixation on inevitable collapse. Authors like Becky Chambers, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Cory Doctorow began imagining futures where humanity actively worked to heal the planet rather than exploit it. Their stories, soon recognized as part of the solarpunk genre, blended themes of renewable energy and grassroots rebellion, challenging corporate and political stagnation with visions of systemic change.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future (2020) embodies many of these ideals. Set in the near future, the novel follows a global effort to combat climate change through technological innovation, policy reform, and grassroots activism. Instead of merely depicting catastrophe, it presents viable solutions, reinforcing the belief that large-scale transformation is not only necessary but achievable through collective action.

Cory Doctorow’s The Lost Cause (2023) similarly embraces solarpunk themes in its portrayal of a world grappling with the climate crisis. Set three decades in the future, it follows the romance of two young activists amidst an era of sweeping change. Massive clean-energy projects are thriving, disaster relief efforts are widespread, and millions are trained annually to mitigate floods and superstorms. Yet, resistance remains—some Americans cling to nostalgia, fueled by misinformation and resentment, rejecting the reality of climate change.

Another key example is Becky Chambers’ A Psalm for the Wild-Built (2021), which explores a solarpunk future from a quieter, more philosophical angle. Set in a world where humanity has chosen a sustainable path, the story follows a tea monk who embarks on a journey of self-discovery, only to encounter a sentient robot—one of many that retreated into the wilderness centuries ago. The novel considers the themes of balance, curiosity, and the search for meaning in a world that has learned to live in harmony with nature rather than dominate it.

The Philosophy of the Dreamer

Solarpunk’s appeal is more than just its green technology or lush cityscapes—it’s the philosophy of the dreamer that drives the genre. In a world where environmental catastrophe often feels inevitable, solarpunk turns to the visionaries, the idealists, and the rebels—not because they have all the answers, but because they refuse to stop searching for them.

The philosophy of solarpunk is one of counter-culture, but not in the nihilistic sense of cyberpunk or steampunk. It is a rejection of corporate greed, fossil fuel dependence, and social isolation, replacing them with localized solutions, renewable energy, and interconnected communities. These works remind us that even in a world damaged by past mistakes, there’s still room for resilience, for action, and for hope.

The Aesthetics of the Solarpunk World

In visual media, solarpunk is defined by a blend of nature and technology, where green roofs, solar panels, and vertical gardens dominate city skylines. While cyberpunk revels in neon lights and rain-soaked streets, solarpunk embraces sun-dappled landscapes, community gardens, and wind-powered airships. The aesthetic is a fusion of Art Nouveau, Victorian, and modern design—cities that feel alive, not just with people but with the plants and ecosystems they nurture.

One of the most iconic representations of solarpunk aesthetics in film is Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Though predating the solarpunk label, it embodies its ideals: a post-apocalyptic world where nature is reclaiming itself, and the protagonist, Nausicaä, seeks harmony rather than domination over the environment. Miyazaki’s later works, such as Castle in the Sky and My Neighbor Totoro, further explore themes of ecological balance, decentralized communities, and technology that coexists with nature rather than replacing it.

The Philosophy of Regeneration

Solarpunk is one of the first sub-genres to focus on regeneration—the idea that humanity can not only stop harming the planet but actively heal it. This philosophy stands in contrast to cyberpunk’s transhumanism, which often focuses on surpassing the limitations of the human body through technology. Solarpunk, instead, asks: what if our evolution isn’t about leaving nature behind, but embracing it more fully?

The solarpunk world is a world of symbiosis—of individuals using technology not to dominate but to restore. Cities become gardens, energy is drawn from the wind and sun, and architecture is shaped by natural forms rather than rigid concrete blocks. Thematically, this means prioritizing local, resilient communities over globalized corporate control. It also means rethinking progress—not as unchecked growth, but as sustainability and renewal.

One of the most striking examples of solarpunk themes in literature is Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974). Though written decades before the solarpunk movement took off, it presents an anarchist utopia where people live in balance with limited resources, valuing cooperation over competition. Le Guin challenges readers to reconsider what “progress” means, urging us to imagine futures not dictated by capitalism but by mutual aid and ecological responsibility.

Solarpunk in Architecture

The Solarpunk genre has had a significant impact as part of a broader architectural movement that embraces the mixture of nature with man-made forms.

At present, the closest thing stylistically to Solarpunk architecture might be Singapore’s Garden City: a political initiative introduced by Lee Kuan Yew in 1967 to transform the dense city into an urban environment brimming with greenery.

In recent years, Singaporean architecture has produced dozens of stunning projects evoking the Solarpunk ethos: the Supertree Groves, the Cloud Fountain, the Jewel Changi Airport and the Marina Bay Sands are but a few prominent examples. Such projects regularly make waves on the Solarpunk Reddit to varying degrees of approval, and some Redditors have offered mitigated praise for the city with the slogan: “Singapore minus cars = Solarpunk”.

Other international examples include cities with green walls and vertical gardens on skyscrapers, a growing movement in itself. In Sydney, Australia, Central Park emerges as a unique space in the city-centre, with these vertical gardens that were some of the first in the world.

Green wall systems provide organic shading. Less heat is reflected, in turn, reducing urban temperatures. It provides energy efficiency and savings due to its thermal insulation – reduction in energy consumption for cooling. It emits oxygen, absorbs CO2 and captures particles of pollution which improves the quality of air in cities.

Solarpunk: Revolution or Utopian Fantasy?

Solarpunk as a genre has faced its fair share of criticism. Chief among these is the accusation that it is too idealistic—that it paints an unrealistic picture of what is possible in the face of corporate greed and political inertia. Some argue that it underestimates the difficulty of systemic change, offering a vision that feels more like wishful thinking than a real path forward.

Yet this criticism misses the point. Solarpunk is not about claiming the future will be easy—it is about insisting that a better world is worth striving for. It rejects the idea that dystopia is our only fate and challenges us to envision practical steps toward a more just and sustainable society.

Unlike cyberpunk, which often embraces cynicism, solarpunk acknowledges hardship while refusing to give in to despair. It reminds us that rebellion is not just about tearing systems down—it is about building something better in its place.

As we move into an era of environmental crisis and technological acceleration, with the extinction of insects, desertification, deforestation, pollution, air quality and microplastics in our cities – Solarpunk’s message feels more relevant than ever. It calls on us not to critique the world as it is, but to imagine—and create—the world as it could be.

Subscribe to the Blog for more essays.

Follow my video essays on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEAl9k5kbD8rkXJLdgnAJ0w

What do you think of the Solarpunk Genre?

Leave a comment below.