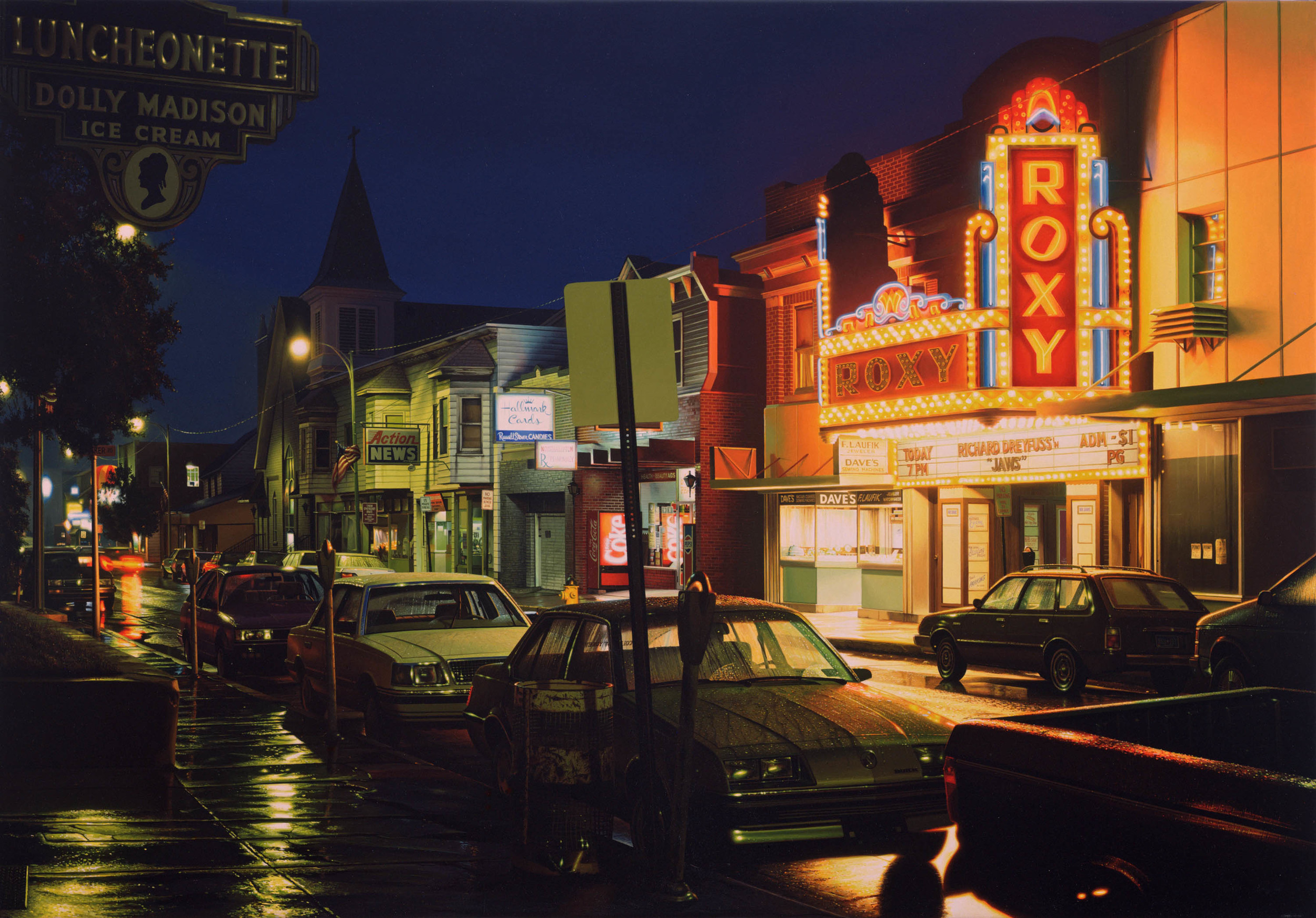

In the 1970s, Davis Cone travelled America and painted the last remaining golden age cinemas. His mission was to paint as many as possible before they were demolished and replaced by new shopping malls and parking lots.

Cinemas were the last buildings standing of the 1920s and 30s, the remaining piece of what was once the Golden Age of Hollywood and the art deco style of architecture. They had stood the test of time because they were to some extent, private buildings with public purposes. They were places where the community gathered to enjoy entertainment and were difficult to replace.

Travelling across the country, Cone depicted them in a photorealistic style, creating pictures so realistic that it feels as if you can almost walk right into them.

His paintings are reminiscent of Edward Hopper, an artist most famous for his work Nighthawks. Like Hopper, Cone captures the mood of a scene, often at night, with a haunting and eery atmosphere.

There are very few people in his paintings, and so we are left to consider the glamour of Hollywood in isolation. What does it mean when the places we love fall into ruin and neglect? What does it mean when the golden years are gone, and all we have left is a painting?

This is the world according to Davis Cone.

The Art Deco Period

The 1920s saw the rise of film as a mass entertainment medium. It was the Golden Age of Hollywood, with the United States producing 800 feature films a year, an output that has not been matched since. Notable stars were born, including Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, showcasing a vision of America to the rest of the world.

That vision represented technological and artistic mastery.

The same thing was happening in architecture. The 1920s and 30s were the peak of the art deco movement. Art deco was an architecture style typified by geometrical shapes and patterns, luxurious details and expensive materials of gold, ivory, and later on, stainless steel. It too was a celebration of all that humanity had accomplished.

Large buildings, like skyscrapers and cinemas, were a key part of the movement. They were places where architects could flex their creative muscles in the new style. There was a grandiosity to art deco that was beginning to appear in skyscrapers, suddenly being built across the major cities. The most famous example was the Empire State Building, at the time the tallest building in the world.

On the other end of the scale were dance halls, built in the art deco style, with organs and red curtains. Many of these were the precursor to modern cinemas and were often converted into cinemas over time.

Other cinemas of the period were purpose-built venues, creating a new entertainment place in big cities, for the general public to experience the new medium. It was a time when screens and moving pictures were a public spectacle, which everyone wanted to take part in.

As the decades wore on, however, things began to change. By the 1970s, art deco cinemas were falling down. Many were bulldozed and replaced by Brutalist-style malls and parking lots, with clean lines and concrete, replacing the old detailing.

The grandeur would be forgotten, were it not for photographs, and the photorealistic paintings of Davis Cone.

Cone spent fifty years painting these crumbling cinemas. His process was simple. He photographed a cinema over the course of several days to use as a reference for each painting. He captured a mood in each work, documenting the building at dawn, dusk, at night and throughout the hours in between. He captured the cars driving past, and the occasional shadow of a person under an awning or huddled in a doorway.

His paintings did what photographs are meant to do: they preserved the memories of a place to celebrate a time and culture that no longer existed.

It was a theme that repeated often in the history of film. One notable example can be found in the Oscar winning film, The Cinema Paradiso.

A film that explores the life of projectionists, another part of movie history that has faded, as quickly as the cinemas they once worked in.

(Spoilers ahead)

The Cinema Paradiso

The Cinema Paradiso tells story of a young boy named Salvatore Di Vito, nicknamed Toto, as he grows up in Post-War Sicily. Each day, he sneaks into his local cinema, spending time trying to win over the attention of the local projectionist, Alfredo.

Alfredo eventually warms to Toto and teaches him how to use the projector.

With Toto’s father lost to the war, Alfredo becomes Toto’s new father figure, looking after him and caring for his wellbeing, much to the initial chagrin, and later acquiescence, of Toto’s widowed mother. The boy and the projectionist make an unlikely friendship, working together and watching films through the small projection window.

But their friendship is marked by tragedy.

One day, a nitrate film catches fire in the projection room, causing a huge explosion that leaves Alfredo blind. There is a lot of symbolism here. The idea of a projectionist going blind, unable to see the works he once valued.

In his place, Toto takes over, being the only man in the town who knows how to work the machine. Toto slowly learns to see the world differently by creating his own films on a new home camera. It is in the process of filming his own projects that he spots the girl, Elena, and falls in love.

When the war breaks out, Toto is conscripted into the army and his love Elena, has to move away with her family to safety. The projectionist, Alfredo, encourages Toto to keep making movies and pursuing his life dream.

Decades later, Toto returns to Sicily for Alfredo’s funeral. There, he discovers a compilation reel of film. It is all of the kissing scenes that Alfredo removed from films over the years, at the bidding of the local priest. Playing the scenes through the projector, Toto can only cry about what once was.

The Cinema Paradiso represents, in many ways, the nostalgia of going back to a place we used to live, and reconnecting with everything we left behind. From our modern perspective, the film itself evokes a kind of nostalgia. The world of projectionists, nitrate film and celluloid, everything shown in the film, to a large extent no longer exists.

Over the last decade, film has been gradually replaced by digital. Many of the projectionists who once worked in those projection rooms, no longer have jobs there anymore.

The photographer Joseph Holmes, much like Davis Cone, spent some time travelling America and photographing these old projection rooms; sacred spaces that very few people had access to, before they were demolished or renovated. “I sometimes think of my photography work as a ticket into places where I would not otherwise by allowed,” Holmes explains.

Projection rooms used to be made up of old film posters, film equipment, “weird graffiti, and dusty forgotten toys.” They are places where people have spent a long time alone, and so they bear those imprints and memories of many years and decades.

But today, over 90% of cinemas have transitioned towards digital, leaving film behind it, and with it, projectionists.

“With the transition to digital, the days of film – real film – are fast coming to an end. Go into a movie theatre nowadays and sit down in the dark, and the picture on the screen won’t be created by a light beaming through a strip of celluloid spinning through a film gate, but by pixels. As for projectionists? Locked alone in a booth, visible only as a silhouette hastily snatched through a small window beaming with light, the projectionist is a dying breed – and few are even noticing.”

The projection rooms are changing, and the old rag-tag image is shifting towards modern sleek lines and metallic boxes. “Inside the booth, it’s like night and day,” says Holmes, “Almost all of those familiar rooms with reels and editing tables and platters are gone. The projector is now a featureless box connected to a laptop.”

And as the progress goes on, and as the years go by, the only thing left of the projectionist are a bunch of photographs, and the only thing left of the cinemas, are a bunch of photo-realistic paintings.

So, time goes on, and we keep what we can of the past.

–

Follow me on Twitter: @JoshKrook

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEAl9k5kbD8rkXJLdgnAJ0w

My Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/newintrigue?fan_landing=true

Merch: https://www.redbubble.com/people/jkro550/shop?asc=u

Subscribe

Fill in your email address to subscribe to future posts on New Intrigue.