In the 1920s, Ernest Hemingway visited the galleries of Paris to see the works of Paul Cezanne, a painter who had an incredible impression on him.

He later said of these visits:

I was learning something from the painting of Cezanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions I was trying to put in them. I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides, it was a secret.

Hemingway was learning that capturing something as honestly as possible was not enough. Something more was needed to make his art come alive.

Cezanne, the French post-impressionist painter, seemed to know the answer. In his style of using bold colours, in a muted collection of impressions of a landscape or figure, Cezanne could go beyond the mere capturing of reality and do so much more than that.

Exploring the works of Cezanne reveals the importance of nature, the role of the artist in showing us what it means to be human, and the use of art to confront us with the exaggerated truth of our surroundings.

This is the world according to Paul Cezanne.

Paul Cezanne was born in the city of Aix-en-Provence, in the South of France, a city well known for its natural beauty and situation near scenic mountains and hills. This beauty had an indelible effect on the young Cezanne, who spent much of his youth gaining an appreciation for the sights, sounds, tastes and touch of his natural environment.

A year below him in school was the young (and later famous novelist) Emile Zola. They quickly became friends and together would venture out into the countryside, exploring the dirt paths and beaten trails into the woods and meadows.

They would lose themselves in the surrounding wilderness, on summer or winter days that would stretch endlessly before them, unfurling year by year. It was in these moments, these places, these touches and tastes and sounds, that Cezanne would gain inspiration for his later paintings. It was in these hills and mountains that he would gain the natural subjects of his work.

Emile Zola wrote of their teenage years together as if of something out of a dream; a glorious time of adventure and exploration that taught the young Cezanne much about beauty and the vitality of life:

On holidays, on days when we could steal from studying, we escaped on wild rambles across the countryside; we needed fresh air, full sun, lost paths at the bottom of gullies, which we claimed as conquerors. Oh, the endless strolls across the hills, the long rests in the green hideaways, close to a little stream, the walk back through the thick dust of the main tracks, which crunched under our feet like fresh snow!

…

In winter, we loved the cold, the ground frozen with ice which cracked merrily, and we would go and eat omelets in the neighboring villages, reveling in the clear sharp air. In summer, all our meetings were on the riverbank, for we had a passion for water; and we would spend all afternoon paddling about, living there, coming out only to lie naked on the fine sand, warmed by the sun.

…

And our loves, in those days, were above all the poets. We didn’t stroll alone. We had books in our pockets and our game bags. For a year, Victor Hugo reigned among us as an absolute monarch. He had captured us with his high style and powerful rhetoric… We walked in time to the beat of his verses, echoing like a trumpet blast.

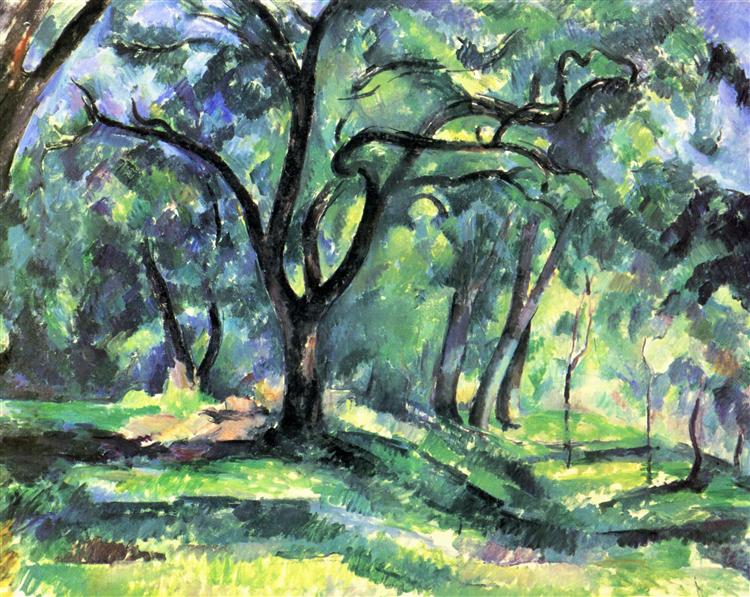

The beauty and poetry of nature became a consistent theme in Cezanne’s later works. Some of his most well-known paintings are of the countryside around Aix-en-Provence. This includes his painting of a forest – with washed out impressionistic leaves and soil, and his painting of Mont Sainte-Victoire; the landscape showing his hometown and its surrounding mountainsides, in all of their natural glory.

One of his most famous paintings, of a group of bathers, likewise captures the spirit of his youth. The bathers, like the young Cezanne and Zola, lie carefree at the edge of a lake, congregating on the soil, to enjoy the heat of the sun and the cool of the water on their bodies. It is a celebration of humanity and nature in perfect harmony. At the same time simple, and yet incredibly profound.

There has been much written about Impressionism as an art style, and what it means to have washed out colours, in hues that are at times brighter than reality. In my view – the hues that Cezanne used in his paintings are the colour of memory. We remember our past as bright, the colours faded and yet vibrant and thrumming with life. It is the beauty of memory that everything ends up with that same summer glow, as if the grey monotony has been washed out of the world. In retrospect, everything looks like a dream. The artist is nothing more than a philosopher of colours, painting the idea of memory and time into being.

This is perhaps most clear in Cezanne’s paintings of everyday objects and in his portraits of individuals. By accentuating the colours of fruit and the vibrancy of an apple or orange, he creates a picture that in and of itself, gets across the feeling of biting into a piece of fruit. The sensation of the juice on your tongue and the brightness that seems to spark from the simplest taste of something sweet.

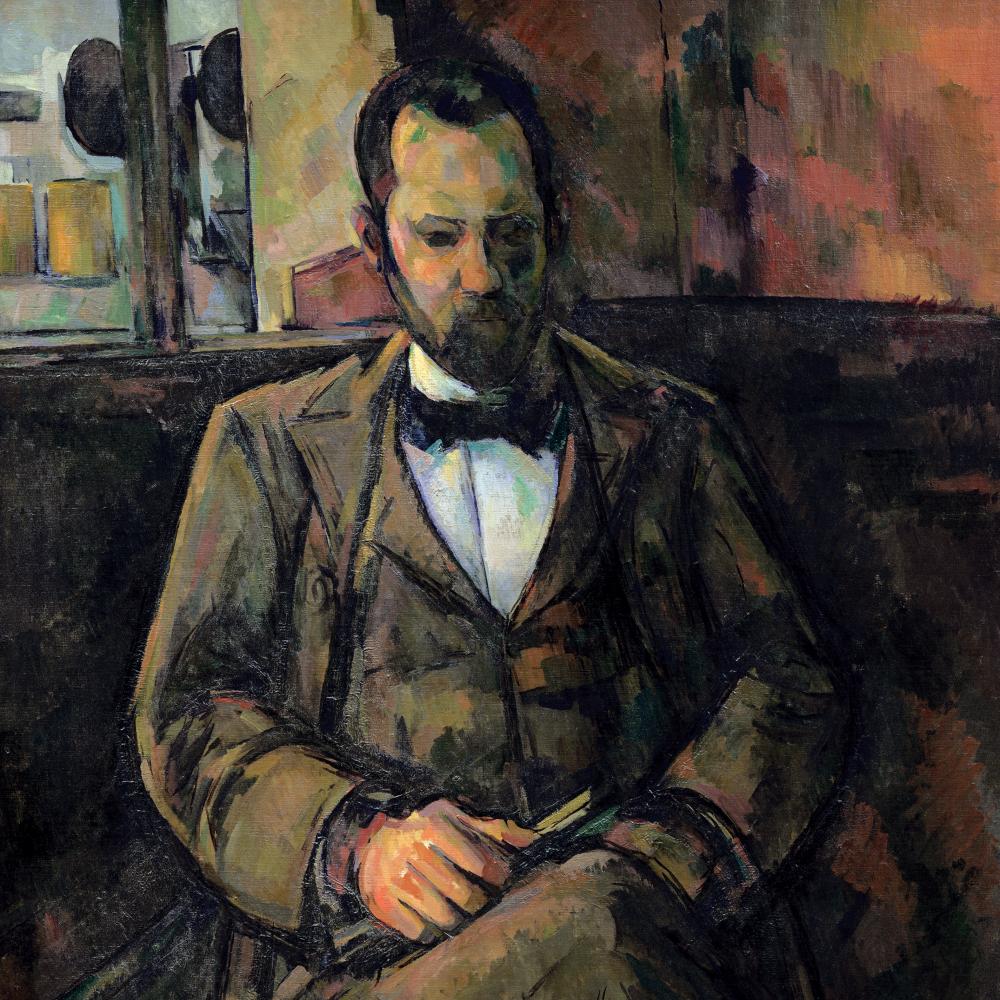

His portraits have a more reserved, darker-tinged feeling to them, with his subjects appearing often resigned or muted – in a clear contrast to the faded hues and colours they are painted in. Nevertheless, they are painted in the faded greys of memory, the feeling, and indeed, the impression of the past – long lost and almost forgotten.

Despite their beautiful way of seeing the world, or perhaps because of it, both Cezanne and Zola fell victim to the typical nihilism fated to young romantics.

By seeing the world in glowing terms, it was inevitable that they would both be confronted by reality. Particularly in the form of people who failed to live up to their social and moral ideals. In a letter to Cezanne, Zola wrote:

I find myself surrounded by such insignificant, prosaic beings, that I’m delighted to know you, you who are not of this century, you who would invent love, if it were not a very old invention, as yet unrevised and imperfect.

Cezanne was himself confronted by the reality of the world, and yet he found solace from such dark thoughts in the pursuit of art. His emotions did not hinder him but acted as a conduit for his work. “A work of art which [does] not begin in emotion is not art,” he wrote at the time, making clear that his emotions were a muse to push him forward, rather than hold him back.

He learnt from Hippolyte Taine, a famous art theorist, that the role of the painter was a higher calling than the mere capturing of reality. The artist could help us grow our understanding of the world, and ultimately, show us what it means to be human. By showing us the harshness of reality, and the emotional truth in it, from a safe distance, the artist could give us space and time to think and reflect upon who we are.

In 1866, Cezanne read Taine’s book, Voyage en Italie, where he describes just such a phenomenon:

In open country I would rather meet a sheep than a lion; but behind the bars of a cage, I would rather see a lion than a sheep. Art is exactly that sort of cage; by removing the terror, it preserves interest. Hence, safely and painlessly, we may contemplate the glorious passions, the heartbreaks, the titanic struggles, all the sound and fury of human nature elevated by remorseless battles and unrestrained desires. And surely, then it has the power to move and to stir. It takes us out of ourselves; we leave the commonplace in which we’re mired by weakness of our faculties and the timidity of our instincts.

…

The spectacle and the repercussions enlarge the soul; we feel as if we are in front of Michelangelo’s wrestlers, tremendous statues whose immense muscles and tendons threaten to crush the pygmy people who look on them; and we understand how in the end these two great artists live in a realm of their own, far from the public domain, in the land of art.

It is a beautiful way of picturing the artist. The person in society who, from a distance, shows us who we are.

Recently, I’ve been contemplating whether there are some things that are too sacred to be turned into art. Taine and Cezanne would seem to suggest that nothing is too sacred. That, in fact, in putting something down on paper, or on the screen, we are, in that moment, doing a sacred act.

For it is only when we can look at something, that we can understand it.

–

Follow me on Twitter: @JoshKrook

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEAl9k5kbD8rkXJLdgnAJ0w

My Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/newintrigue?fan_landing=true