My interest in romanticism comes from the way in which it might address some of the key problems of modern technology. Today’s technologies – our phones and gadgets, screens and notifications – disconnect us from the real world, other people and ourselves, triggering a crisis of both identity and authenticity.

I’ve written before about Neil Postman and Byung-Chul Han, critics who pointed out some of these problems.

But I think it’s equally important to consider possible solutions.

If modern technology dehumanizes us, then is there something that can re-humanize us? If modern technology disconnects us, then is there something that can reconnect us? … to nature, to other people, and to ourselves?

Enter the early German Romantics.

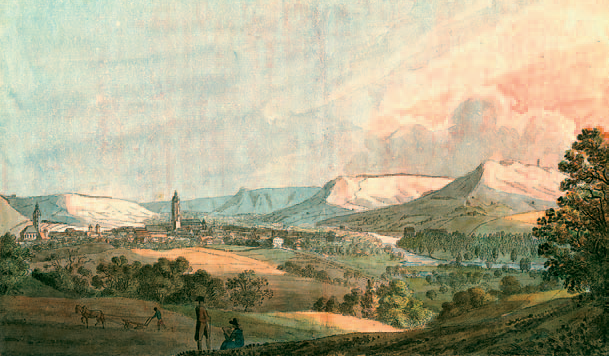

In the late 1790s, a group of German writers met in salon events held in the city of Jena. Their aim, as is commonly thought, was to grapple with a response to the scientific ideologies springing out of the Enlightenment. Crucially, the hyper-rationality and logic which has come to dictate large contours of modern life, such as the modern university system.

At the time, the Enlightenment ideas of reason and rationality had taken much of the awe and mystery out of the natural world and out of human experience. Subjective experience had been replaced by objective fact. Science had turned nature into a bland thing, without any magic or awe to it.

Humans became, as a result of this, disconnected from nature, themselves and other people. A core part of this was a disconnect from the senses themselves, and through that; from art, from spirituality and from religion.

The German Romantics aimed to counter this development with their own system of thought. A system that became known as Romanticism, and originates our understanding of the word Romantic, which in this context denotes more than just romance.

The Romantics aimed to re-frame the objective conceptual understanding that people had of the world around them and to recenter our ideas on the subjective, sensory experience of individuals. As Frederick Beiser puts it in his brilliant book, The Romantic Imperative :

The aesthetic revolution of the young romantics was much more radical still, going far beyond any plans for the reform of the arts and sciences. For its ultimate aim was to romanticize the world itself, so that the individual, society, and the state would become works of art. To romanticize the world meant to make our lives into a novel or poem, so that they would regain the meaning, mystery and magic they had lost in the fragmented modern world. We are all artists deep within ourselves, the young romantics fervently believed, and the goal of the romantic program is to awaken that talent slumbering within ourselves so that each of us makes his life into a beautiful whole.

To achieve this unity with the world, the young romantics encouraged the creation of art and poetry. It is the artist who creates their own subjective experience of the world through reproduction and adaptation, they believed.

In simple terms…

There is a significant difference between the scientific facts of a tree and a poem about how a tree makes someone feel, and then again, how a tree is connected to the ecological system that makes up nature, thereby bringing us into a higher state of awe and understanding of our place in the world.

It is not surprising that the romantics turned to poetry, literature and art for their mission, for it is through these mediums that we can explore our subjective sensory experience of reality. To romanticize the world, said Friedrich Schlegel, a key member of the movement, is “to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite.” This meant looking to our external senses of touch, taste and so on, but also to our internal senses – and connecting our external reality to our internal world.

We dream of a journey through the universe. But is the universe then not in us? We do not know the depths of our spirit. Inward goes the secret path. Eternity with its worlds, the past and future, is in us or nowhere.

In practical terms, we can summarize their advice as follows: re-engage the senses, accept subjective experience of reality, create your world in art and make life an artwork by romanticizing it. Only then can we unify with the world around us and stop feeling disconnected.

If this seems esoteric, it probably is. But it’s worth contemplating how similar ideas are now being peddled even in practical realms. The fad of mindfulness, for example, is nothing more than a reengagement of the sensory exploration of one’s surroundings. As is the idea of forest bathing, or the drop-in painting and art classes held with paint by numbers style studios where “anyone can be an artist.” The ideas of the romantics are alive and well in these repackaged, corporatized versions of the key ideas, even if the ideas have been weakened in the corporatization process.

We might ask here whether the metaphysical ideas of the romantics – the idea of us unifying with nature, others and ourselves – can be so neatly separated from the practical aspects – appreciating nature and our senses. Might mindfulness, devoid of any spirituality, be enough? Can’t we simply appreciate a painting without romanticizing our world?

In some ways, the early German romantics answer this objection by critiquing the related idea of hedonism. If we are to engage the senses, why not just become hedonistic? Surely binge watching Netflix counts as appreciating art and imagining the world?

Here, Novalis, one of the key figures of the movement, responds that the problem with hedonism is that it does not encourage our humanity or individuality. The hedonist:

Devotes himself to a life of comfort. He makes his life into a repetitive routine, and conforms to moral and social convention in order to have an easy life. If he values art, it is only for entertainment; and if he is religious, it is only to relieve his distress.

There are many criticisms that have been leveled at the philosophy of romanticism. The most basic one is that it is impractical or elitist. There is something intuitively false about this claim. The idea that connecting with nature is elitist seems particularly absurd, as does the idea that appreciating the world through art is high brow. It is one of the unique things about being human, as compared to other animals, that we have the capacity to build things, to create art, to imagine, to dream and to appreciate our surroundings in a sophisticated manner. Calling these things elitist is the same thing as denigrating the disadvantaged to a life less than human. This is why modern society is so dehumanizing, because we so value the pragmatic and practical, that we are willing to give up the very traits that make us human for the functionality of an animal or machine. This capitulation is then justified on both sides of politics as a natural course of events (on the right as a function of the market, and on the left as a function of privilege).

A second critique goes to the outcome of the romantic movement. With its metaphysical focus on unity, many of the German romantics would later tie their ideas to spirituality and religion. In a secular world, it is difficult to reconcile this turn with the hyper-rational manner in which we view the world. Such a critique is not fatal to the movement however, for it is not true that romanticism necessitates religion per se, in the same manner as the fact that appreciating poetry, higher beauty, or the unity of the world, doesn’t necessarily make someone religious.

A final and perhaps most damning critique is that the romantic movement was the precursor to Nazism. The idea of making the world an artwork, or perfect in some manner, can justify political movements that are intolerant to the outsider or socially-defined “imperfect” of humanity. There is perhaps some level of truth to this criticism. Depending on one’s perception of art and beauty, politics can define the other as ugly in some manner that justifies cruelty at an extreme scale.

A good answer to this critique however comes from the German film, Never Look Away.

(Spoilers Ahead)

The film explores the life of a German artist as he lives through the Nazi period in Dresden, the Soviet Occupation of East Germany and the American occupation of West Germany.

Under each regime, the painter paints in the style of the dominant political force in the occupied territories. Under the Nazis and under East Germany Soviet rule, he paints propaganda. His work is notably beautiful, but he despises it and feels a strong disconnection from it.

Eventually, he escapes to West Germany. There, under the Western mindset, he creates modernist abstract art, which is, in its own way, equally inauthentic. He still feels disconnected from it.

The reconciliation of the film is in the way that the central character realizes that the purpose of art is to tell the truth. The reason the propaganda was damaging was because of its untruth and inauthenticity. The modern art he created was equally inauthentic. Copying a style or trend, the film suggests, is not true art at all.

Eventually, the protagonist creates recreations of photographs of the war, in painting, capturing the truth about what happened. The movie is based loosely on the life of a real artist of the period, Gerhard Richter.

It’s central message is so groundbreaking because it answers the common refrain that art can be manipulated for the purposes of evil. Perhaps this is not true if the art itself is an attempt to capture the truth about reality. Perhaps evil is always a manipulation of reality. These are big questions.

Inspired by Never Look Away, it is perhaps possible to add a rejoinder here to the romantic movement to complete the thought process that they began. If we are to romanticize the world, we might suggest, we must make sure to do so in a way that captures the truth of our reality, rather than becoming subservient to propaganda and ideology.

It is not enough to add magic and mystery to the world through art, if that art is inauthentic and the magic and mystery is false.

If we are to re-engage the senses, it should be to capture the truth of our sensory experience, rather than to create an ideological truth conforming to the social and political expectations of our society. To do so requires a critical distance and disconnect from the prevailing forces of one’s society, the dogmas of nationalism and xenophobia for one, and an integration of the philosophy of beauty itself, an appreciation for the world, for nature, and for our place within it. It is this fundamental truth we seek, in the same vein as Kafka suggests that we must read literature to hack away at the frozen seas inside ourselves.

When we think about the modern problems we are facing around technology and disconnection, romanticism might be one solution to the problem. Far from engaging in a simple process of mindfulness or other corporatized versions of sensory exploration, the core ideal of romanticism is to rethink one’s entire worldview so as to romanticize the world and to integrate it into a singular authentic whole. Such a process requires not a wholesale adoption of one’s political and social environment, but a critical introspection and extrospection leveled at the natural and internal worlds of one’s own being.

That in itself might be enough.

Follow me on Twitter: @JoshKrook

Buy my books here.