The year is 2014 and Tony Abbott, the Australian Prime Minister, announces a series of cuts to public spending across healthcare, education and unemployment benefits. Modeled off of the austerity programs sweeping Europe at the time, the cuts aimed to balance the federal budget and privatize public services.

The UK, Greece, Spain and Portugal have all adopted austerity programs in the past, and the results have been crippling debts and stagnating economies. Far from revitalizing Europe, austerity entrenched its despair. If these countries are anything to go by, Australia’s austerity programs fair no better. Luckily, the program of cuts never came to Australia. Facing broad opposition by the general public, the government backtracked on their proposed austerity budget of 2014.

The backlash at the time was heralded as a victory for the progressive movement in Australia. Finally, Australia was taking a stand against the conservative forces aiming to reshape the country into the haves and have-nots, the rich and the poor, the old and the young. Or as the Treasurer Joe Hockey put it at the time, the “lifters and leaners”. Instead of this, the idea prevailed that Australia was a place of the ‘fair go’ for all people. A place where everyone had a chance to thrive and strive, regardless of their economic background, social class or status. The celebration of the progressive movement began in earnest.

But that celebration was premature.

Despite the defeat of austerity, 2014 marked the year that Australia became a conservative nation. On a number of issues, ranging from refugee rights to environmentalism to the foreign aid budget, a culture of fear and resentment, which started with the election of Tony Abbott as Prime Minister in 2013, cemented the trajectory of Australia towards a narrow-minded, right-wing and insular worldview. The country, reshaped in Tony Abbott’s image, has since become risk-averse and hostile to outsiders. Having dodged the financial crises of Europe, Australia fell for European’s alt-right conservative social policies, falling under the thrall of racism, sexism and an anti-scientific anti-intellectualism agenda.

Caption: Australia’s foreign aid budget over time. (Source).

Above, observe the declining state of Australia’s foreign aid budget since 1974. This graph, more than any other, shows how insular the country has become. As opposed to engaging in the world stage, taking its part as a wealthy country in the assistance of the poor and the vulnerable, Australia has adopted an ‘Australia First’ policy. Hacking and slashing foreign aid, dismantling the entire AUSAID department (through which aid was traditionally delivered overseas) and, regardless of the government in power, decreasing spending on charity programs in foreign countries. When the world is suffering, the people of the world can surely ask, where is Australia? The response? Australia will not answer the call.

So how did this happen? The conservatives changed the conversation in Australia with one tactic: fear. The Liberals have long held a policy of governing through fear. Fear of the immigrant. Fear of the cost of carbon (‘axe the tax’). Fear of foreigners. Fear of the young. Fear of the old. Fear of taxes. Fear of green energy (including wind farms).

In psychological terms, fear is the most effective means of persuading someone about a particular topic. Fear bypasses our conscious mind to speak to our subconscious; it can evoke a fight/flight response and threaten our common sense through deep psychological impulses. It is one of the most effective political tools and is often used in both campaigns and political advertising. The danger of fear is that it is irrational. Used against us, it can make us act against our best interests.

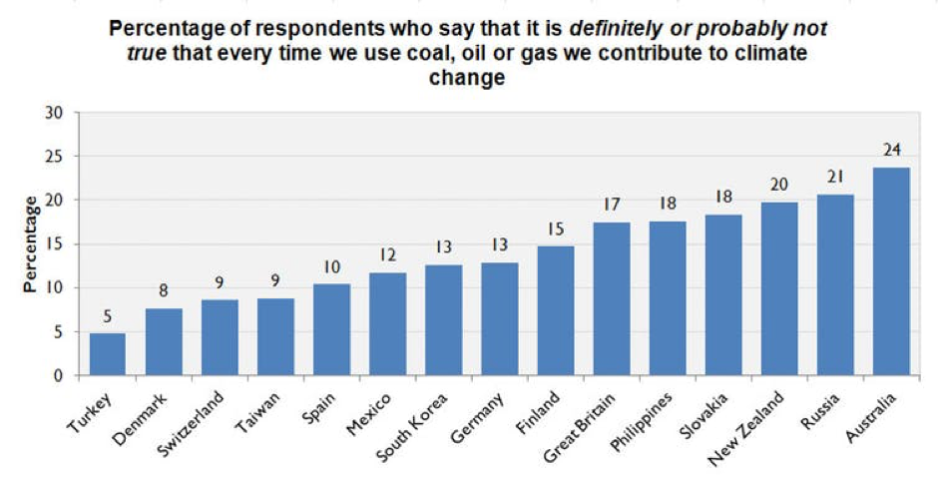

Let’s start with the environment. What began in 2013 as a campaign against the carbon tax (something which sounded scary because it could raise the cost of petrol), was resumed in the 2019 election campaign as a campaign against increased fuel costs. The Liberals ran a fear campaign about Labor seeking to “ruin the weekend” getaway by car. At the same time, Prime Minister Scott Morrison tried to tamp down fears about coal. In an earlier stint, he famously brought a piece of coal into parliament, waving it in the air and stating: “Don’t be afraid. Don’t be scared. It won’t hurt you. It’s coal.”

In a world currently consumed by the hottest temperatures on record, it is difficult to understand how such a culture of fear can catch on. In the UK, where Extinction Rebellion shut down London bridges last month to raise awareness for climate change, the government has declared a “climate emergency”. By contrast, Scott Morrison is laughed at overseas for having brought a lump of coal into parliament and declaring, implicitly, that coal is our future. In Australia, only the city of Sydney has declared a climate emergency. Fear is preventing action by shaping public opinion, and changing the perception of what we, as Australians, can do on the world stage.

Caption: Does coal, oil or gas always contribute to climate change? (Source).

Let’s consider refugees next. One of the most famous moments in recent Australian political history is when Prime Minister John Howard declared in his 2001 campaign, “we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.” What followed was years of Liberal policy reshaping the way Australians think about refugees. “Boat people” as they were re-termed, were firstly dehumanized with derogatory language, before being locked up on remote islands on Manus and Nauru. Fear has been used in every election on refugees since 2001. Fear that asylum seekers are drowning at sea, fear that they are entering the country illegally, fear that they precipitate a giant wave of immigration, one so big it will overwhelm the continent.

More recently, in the 2019 election campaign, Scott Morrison’s government adopted the language of Donald Trump. Where Trump talked of Mexicans as rapists and criminals, Immigration Minister Peter Dutton used the same language to discuss refugees detained offshore in Australia’s detention centres. In the midst of the campaign, he said, “we have people that can come to our country from Manus or Nauru, people that have been charged with child sex offences, people that have been charged [with] or have allegations around serious offences including murder”.

In terms of refugees, the fear campaign started by John Howard and Tony Abbott continues. In 2017, almost half (48%) of Australians surveyed believed that refugees arriving to Australia by boat should never be settled here. In the same poll, 40% found refugees to be a ‘critical threat’ to Australia’s interests. Labeled as ‘illegals,’ a dehumanizing label which aims to disconnect refugees from their suffering, refugees have been seen as criminals. Their crime? Fleeing from persecution to a land where they won’t be persecuted.

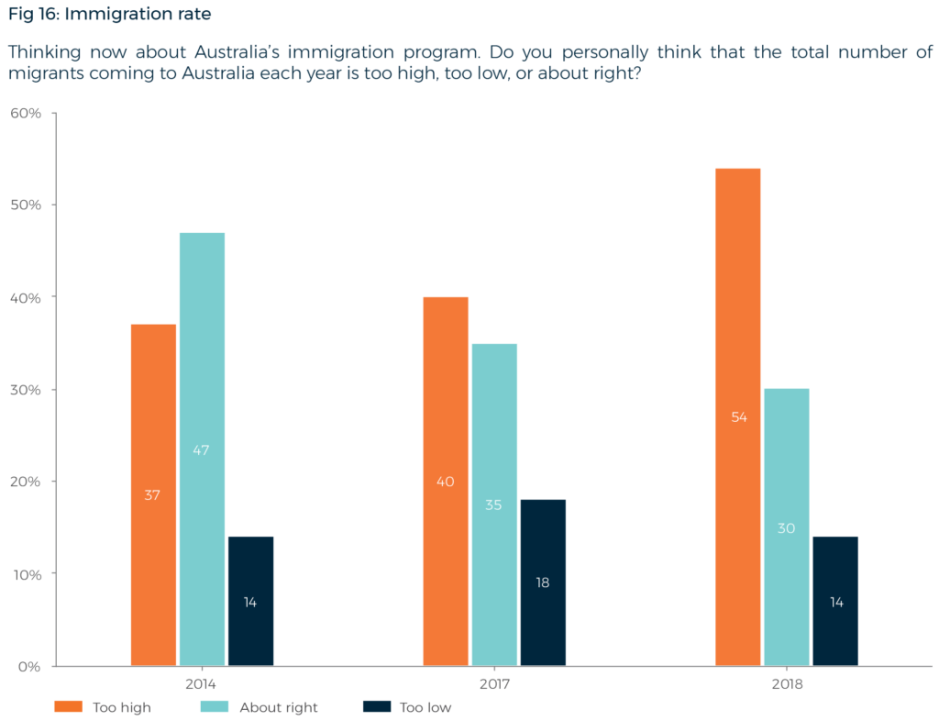

Caption: Australian attitudes towards Immigrants (Link)

More than anything else, fear has shaped the Australian public’s view of who refugees are and why they are coming to our country. This has had a flow-on effect to immigrants more generally. In the graph above, Lowy Institute polling shows Australians turning against immigrants in increasingly large numbers. Data points like this are common in European countries, where immigration is low and so hostilities due to homogeneity principles apply. But in Australia, a country of immigrants where half of the country has a parent born overseas, the data appears strange. It is only when the fear campaigns of the last decade are taken into account, that such a situation appears logical.

Overseas, Australia has become a laughing stock on the international stage. The United Nations, the UK and the US all look to Australia as a sad example of where a country can get lost in its own hubris. In the UK, Boris Johnson, the likely Conservative leader, has promised to implement an ‘Australian-style’ immigration system. By the same token, U.S. President Donald Trump has looked to Australia’s immigration system for inspiration.

Scott Morrison’s election victory in 2019 came as a shock to many Australians this year. But it was the inevitable conclusion of fear, intimidation and right-wing policy concessions. The country, year by year, is becoming more conservative in terms of its social and political outlook. The more we look inward, however, the more the rest of the world will leave us behind in terms of green technology, humane refugee policies and foreign aid and charity. We have to ask ourselves as a country, whether we want to be known as the most selfish country on earth, or a country that cares about the world around us?

Follow the author on Twitter: @JoshKrook