When we see the world through the lens of how things currently are, it is almost impossible to imagine things differently without in some way imparting some of the existing dynamics into the imagined future.

Ask a random person on the street today why they work a nine to five job, and they will give you a variety of personal answers. Insist: No, why do you work nine to five in particular, why that number of hours? And they will give you some derivation of “that’s just the way the world works.” Eight hours is average, and most people work the average number of hours because that’s what average means.

But is it true that “that’s just the way the world works”?

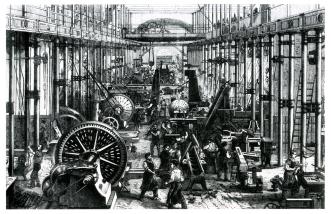

In 1834, Connecticut, what was average meant something completely different to today. Employers in large factories had discovered at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution that factory output was maximised –and more goods were produced- if employees worked up to 20 hour days, 6 days a week.

It was average for employees in factories to do factory work dawn to dusk, in what we now consider unbearable conditions.

We can imagine a man (actually it was mainly kids) on a factory floor in 1834 thinking over his long working hours and saying to himself or a friend, “well, I guess that’s just the way the world works.”

And yet such a man (or kid) would be proven wrong a mere year later.

In 1835, a worker’s strike in Patterson, New Jersey textile mills sparked widespread union protests all along the East Coast of America that caused a change to the number of working hours in factories from an unregulated infinity, to a regulated 10-hour working day.

In 1914, Henry Ford unilaterally reduced his own employee’s workday from 10 to 8 hours, from a 6-day week to a 5-day week. Ford stated at the time: “It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either ‘lost time’ or a class privilege.”

Following the change, productivity at Ford Motors skyrocketed, confirming later managerial theory that being decent to employees boosts overall productivity.

Largely inspired by the story of boosted productivity, other companies followed suit.

The Ford Motors story produced the current employment system as we understand it today and the nine-to-five, five days a week norm that remains the national average.

It is important to remind ourselves from these historical changes and trends that the world does not “work” in any particular way whatsoever. Rather, the way the world ‘works’ or does not work is subject to changes brought about by human beings.

This is particularly the case when it comes to systems that were designed, built and maintained by humans to begin with – such as the employment system.

*

Our Current System Dates Back to 1914; So What’s Next?

It’s sometimes strange to think how little the work hours of the population have changed in the over a 110 years since 1914.

While part-time work, shift work, casual and flexible work practices have all become common, it is still average, and indeed expected, to have and to hold a 9-5 job.

Average working hours of full time workers in Australia

(Australian Bureau of Statistics)

In an article in Strike Magazine, anthropologist David Graeber asks the crucial question: why?

In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that technology would have advanced sufficiently by century’s end that countries like Great Britain or the United States would achieve a 15-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this.

And yet it didn’t happen.

Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless.

Instead of technology being used to free us from a forty-hour week, we have somehow gone the other way, and used technology to reinforce the system that Ford originally established in 1914.

Logically, this makes little sense.

At a basic intuitive level, computers speed up the rate at which humans can work, meaning that, by and large, we should be accomplishing more in less time; begging the question, why are we all spending the exact same amount of time at work? This is particularly perplexing regarding the effect automation has on the basic necessities of human existence like: food, clothing and housing, and the increasingly expanding human population.

One could imagine a 3D printing revolution where food and clothing are available in every household at the press of a button; effectively making ‘working to make ends meet’ an outdated anachronism.

But Graeber goes further to suggest that we’re kind of already there:

Over the course of the last century, the number of workers employed as domestic servants, in industry, and in the farm sector has collapsed dramatically. At the same time, “professional, managerial, clerical, sales, and service workers” tripled, growing “from one-quarter to three-quarters of total employment.”

In other words, productive jobs have, just as predicted, been largely automated away. But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours … we have seen the ballooning not even so much of the “service” sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing.

These are what I propose to call “bullshit jobs.”

With the automation of agriculture and farming, it was expected that the leisure time of the majority of the population would dramatically increase.

This was not simply speculation, but a product of historical consideration. When looking back at feudal times we can gather that the aristocracy and noble class had ample free time, largely due to the diligent work of serfs below them; producing the food and sustenance necessary for their continued survival.

Now that we have machines (and, albeit, a very small percentage of the population controlling machines) producing our food, agriculture and clothing for us, it begs the question; where’s the free time we were meant to get?

Quotes from Graeber’s ‘Bullsh*t Jobs’ appeared recently on the

London Underground.

Graeber suggests that our free time has gone into what he calls “bullshit jobs,” plumped up positions that do nothing for society except produce paperwork and move money between people, apparently for no reason whatsoever.

Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed.

Consider telemarketers being replaced by machines, or bell boys being replaced by automatic rotating doors, or even sales and marketing staff being replaced entirely (no such staff used to exist, and yet now entire industries are devoted to marketing, sales and advertising – why?).

The sheer diversity of products we are exposed to likewise goes beyond what is sane or sensible. At a certain point materialism bombards us with so many choices and so many items that it must make us pause and think, should we even be materialistic at all?

The original Ford motorcar was only in black – now there’s no point arguing for a black and white society today, but if we took the edges off the colour palette… If we got rid of some of the extraneous variations on items so as to give the entire country an extra day off per week – if we cut up extraneous industries and marketing staff and pointless frivolities of employment, then maybe we may be onto something here.

It’s likewise difficult to think of menial tasks in particular, such as cleaning, that can’t already be automated, or soon shall be, to the point where humans no longer need to do them.

We’ve all seen advertisements for things like the KL-310 vacuum cleaner (pictured below), able to clean a floor by itself without any human operator:

And yet this is merely the beginning of such a phenomenon.

Almost all artificial intelligence experts say that we’re verging on a breakthrough on the subject of robotic artificial life by about 2050.

The robotic revolution, and everything that means for human employment, is about to begin.

NB: It is important to note the likely increased automation of industries even before a complete artificial intelligence is created. In the next 40 years things like domestic housework in particular are likely to undergo significant changes into automation and those manual industries will dissolve, likely as is historically the case with such things, into sales and marketing. God knows why.

*

The Robotic (Post-Industrial) Revolution:

There is something very curious about politicians constantly obsessing over people getting jobs in the light of the oncoming Robot Revolution.

Now you might think I’m crazy for believing in such things, but then you will have to call the likes of Stephen Hawking crazy too, which is a much, much more difficult task.

There are already articles on the web asking: “What will happen when Robots Take our Jobs?” The idea is that an oncoming robotic revolution is coming whether we like it or not.

And with it, the capacity of robots to do the jobs typically reserved for humans – including high-end, white-collar professional work. The latest robotic innovations out of Japan can play ping pong (“and even decide to take it easy on opponents by missing a few hits”), use sign language to “talk” to humans and “mimic simple greetings.” This is only the beginning.

Despite almost every single instinct of intuition in my body saying that robots will make our lives easier, which is what we’ve been taught (using examples like the washing machine in the 1950s) –by freeing up our time and allowing us to work on things that aren’t menial, boring office jobs– we have to look to history here and realise that that seems like an unlikely outcome. History has a few examples where this is true, but on the whole it has gone the other way, and this time round…

It may even go the other way.

Toshiba’s “Aiko Chihira” Robot demonstrates hand motions at

Tokyo Electronics Show (Daily Mail)

Despite huge, widespread automation since 1914, we still have the exact same 8-hour workday as workers in Ford did back then. Our work hours are static, unchangeable even, amidst growing and growing automation.

Why do we think getting robots will make any difference here, if other kinds of automation haven’t? Why do we think robots will free up our time, when factory machines and agricultural automation did nothing of the sort?

In fact, scientists are predicting that robots will make our lives even worse. Their predictions are based on the idea that our employment systems will in fact, as has occurred over the last century, remain exactly the same.

Our unchanging systems will, in effect, be the cause of our greatest decline – by obsessing over keeping things as ‘the way the world works’ – the world will change dramatically from under us and ruin all our so-called workings.

Oxford Philosopher Nick Bostrom recently told New Republic:

The subsistence level for digital minds would be a lot lower than for biological minds. Biological humans need to have houses—we need to eat, we need to transport ourselves. Digital minds could earn, like, a penny an hour. The wage level would fall; humans could then no longer earn a wage income. It looks very questionable, in this free-for-all competitive world, that we would find a niche for our small, stupid, obsolete minds.

The prediction is that our current working system would continue exactly as it has for the last century. Except, instead of humans outcompeting each other, robots would outcompete humans. Employers would pay the lowest wages possible, relying mainly on robots, and then instead of redistributing this into freeing up humanity’s time, or distributing the money to humans in general– humanity will simply lose out. Now that’s bloody well grim isn’t it?

How do we prevent that kind of future?

Change the employment system we have now.

*

Failure to ask questions about the future of our society is an implicit endorsement of the direction our society is already heading in.

Contact me at: josh (dot) krook (at) gmail (dot) com

@JoshKrook

My book Essays in AI has just been released in paperback!